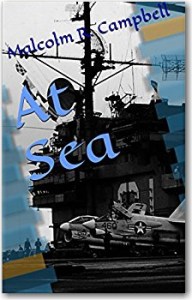

If you were around during the Vietnam War, you’ll probably remember that much of the news coverage dealt with body counts, to show the progress the U.S. was making in ridding the country of the Viet Cong. In my novel At Sea, the protagonist’s grandfather (“Jayee”) keeps his own listing of those from Montana who were killed in the war.

If you were around during the Vietnam War, you’ll probably remember that much of the news coverage dealt with body counts, to show the progress the U.S. was making in ridding the country of the Viet Cong. In my novel At Sea, the protagonist’s grandfather (“Jayee”) keeps his own listing of those from Montana who were killed in the war.

Jayee’s Lists

Jayee’s Lists (The Poor Sons of Bitches who Died) lay faded in a low kitchen drawer beneath batteries, broken pencils, expired dog food coupons, forgotten pink birthday candles, gum erasers, and other unsorted miscellany.

Superimposed over the small battlefield of the ranch, where lambs and eagles met largely unrecorded deaths on a rangeland framed by fences, box elders, cottonwoods, and a narrow creek carrying water off the backbone of the earth in years of drought and years of flood, the old man recorded soldiers’ names and souls.

He read the news from Vietnam with morning coffee and evening spirits, and with a fine surveyor’s hand, he tallied the bare bones of body counts between narrowed-ruled lines in lightweight Bluehorse notebooks intended for the wisdom of school.

After dinner, he walked out through the bluebunch wheatgrass and settling sheep to his ancient Studebaker pickup truck. He carried a sharp yellow pencil and a pack of Chesterfields, tools for doing his sums, “calculating Montana” in a cloud of cigarette smoke from “vintage tobaccos grown mild, aged mild, blended mild.”

On the first page of the first book he wrote, Here are the poor sons of bitches who died. On the last page of the last book, he wrote, The dead, dying, and wounded came home frayed, faded, scuffed, stained, or broken.

On the pages in between, he wrote the name of each Montana soldier who was killed or missing in recorded battles far away. Sipping bourbon, smoking like a lotus in a sea of fire, he ordered, numbered, and divided the names by service branch, by casualty year, by meaningful cross-references, by statistically significant tables, by the moon’s phases and the sun’s seasons, and by the cycles of sheep.

Jayee remarked from year to year that the notebooks grew no heavier with use. He saw fit to include the names of the towns where the dead once lived, fathered children, and bought cigarettes. These names he learnt were also lighter than the smoke.

The current of his words between the pale blue lines of each thin page arose in fat, upper case letters that scraped the edges of their narrow channels. They began as a mere trickle from 1961 to 1964 that grew in volume in 1965 before the first spring thaw, to become a cold deluge that crested in 1968, wreaking havoc across the frail floodplain of pastures and pages, carrying the dark, angry names scrawled with blunting pencil, and broken letters, through irregular gray smudges, over erasures that undercut the page deep enough and wide enough to rip away the heart from multiple entries. There was little respite in 1969. After that, the deaths receded and most of the physical blood dried up by 1973.

The pages were dog eared, marked with paperclips already turning to rust, and fading to pale dust behind the list of towns: RICHEY, WHITEFISH, HELENA, CHOTEAU, BOZEMAN, BUTTE, KALISPELL, THOMPSON FALLS, THREE FORKS, STEVENSVILLE, TROUT CREEK, BILLINGS, CHOTEAU HINSDALE, GREAT FALLS, HARDIN, SACO, SIDNEY, HAVRE, HELENA, GREAT FALLS, HELENA, BOZEMAN, BUTTE, DODSON, ARLEE, REEDPOINT, HAVRE, BIG SANDY MISSOULA, BILLINGS, WHITLASH, ROUNDUP…

Jayee’s tallies added up like this: USA—169 USAF—16 USMC—59 USN—23 TOT—267

The old man made 267 trips around Montana between 1961 and 1972 that no surveying jobs could account for. He said little to the family about it and they didn’t often ask.

During Jayee’s second trip to Havre in 1966, Mavis, a waitress at the Beanery, noticed a stack of 44-inch white crosses sticking out from beneath a tarp in his truck. On each cross, there was a name. When she suggested that Jayee was stealing them from roadside accident scenes, he said he made them per spec to repay old debts.

Mavis asked Katoya if Jayee was all right and Katoya said: “right enough.” He returned to the restaurant multiple times to prove he was right enough and was sitting there on August 31, 1967, when the 77-year-old Great Northern restaurant served its last bowl of Irish stew and closed its doors for good. When the building was torn down the following February, he pounded “an extra cross” into the rubble where the counter once stood and said it was the best he could do.

Months passed and additional stories surfaced about an old man crisscrossing the state searching for the families of the fallen, and of warm conversations lasting long into the dark hours. Jayee remained solitary and taciturn in the face of public or private praise or blame and traveled from town to town methodically, as though he was marking chaining stations along an endless open traverse.

After each individual’s name, he wrote XD (cross delivered), XR (cross refused), or CNF (could not find).

On October 18, 1974, Jayee died (surrounded by old relatives and the close perfume of vintage tobacco) with a freshly sharpened yellow pencil, with a half-smoked pack of Chesterfields, with lists and spirits close at hand, waiting for closure, he always told those who asked about them.

Reverend Jones stood before the mourners in the small church and read the names of those who wished to remember and to be remembered, and one upon one, they created a great hymn that rose up over the banks of their consciousness and flowed down the rivers of their perception in a crowned deluge.

Copyright © 2010, 2016 by Malcolm R. Campbell

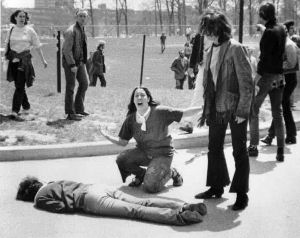

“Women can be heroes. When twenty-year-old nursing student Frances “Frankie” McGrath hears these words, it is a revelation. Raised in the sun-drenched, idyllic world of Southern California and sheltered by her conservative parents, she has always prided herself on doing the right thing. But in 1965, the world is changing, and she suddenly dares to imagine a different future for herself. When her brother ships out to serve in Vietnam, she joins the Army Nurse Corps and follows his path.

“Women can be heroes. When twenty-year-old nursing student Frances “Frankie” McGrath hears these words, it is a revelation. Raised in the sun-drenched, idyllic world of Southern California and sheltered by her conservative parents, she has always prided herself on doing the right thing. But in 1965, the world is changing, and she suddenly dares to imagine a different future for herself. When her brother ships out to serve in Vietnam, she joins the Army Nurse Corps and follows his path. “But war is just the beginning for Frankie and her veteran friends. The real battle lies in coming home to a changed and divided America, to angry protesters, and to a country that wants to forget Vietnam.

“But war is just the beginning for Frankie and her veteran friends. The real battle lies in coming home to a changed and divided America, to angry protesters, and to a country that wants to forget Vietnam.

But I have always wondered. Anna and I might have gotten married in Göteborg (shown in the photo). I would have learned Swedish and looked for a job–with the assistance of the Swedish government as a requirement for being granted asylum. While I thought I might never see the U.S. again, Jimmy Carter granted amnesty in 1977. Would I have come home? Well, probably for a visit. Obviously, I know what happened here that would not have happened if I had chosen Sweden.

But I have always wondered. Anna and I might have gotten married in Göteborg (shown in the photo). I would have learned Swedish and looked for a job–with the assistance of the Swedish government as a requirement for being granted asylum. While I thought I might never see the U.S. again, Jimmy Carter granted amnesty in 1977. Would I have come home? Well, probably for a visit. Obviously, I know what happened here that would not have happened if I had chosen Sweden.

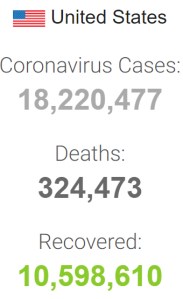

During the COVID-19 invasion, the news has also provided daily body counts, primarily cases, and death tolls. Once again, these figures didn’t tell us much about the pandemic, except that it got better, and then it got worse. As for the collateral damage of grieving survivors, a shattered health care system, lost jobs, bankrupted businesses, and related and unrelated social unrest and violence, we can say with a fair matter of certainty the pandemic has broken just about everything.

During the COVID-19 invasion, the news has also provided daily body counts, primarily cases, and death tolls. Once again, these figures didn’t tell us much about the pandemic, except that it got better, and then it got worse. As for the collateral damage of grieving survivors, a shattered health care system, lost jobs, bankrupted businesses, and related and unrelated social unrest and violence, we can say with a fair matter of certainty the pandemic has broken just about everything.