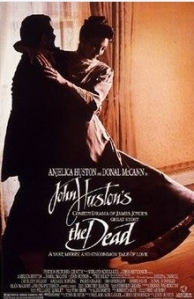

John Huston was dying while working on “The Dead,” a 1987 film closely based on James Joyce’s 1914 short story in The Dubliners collection. The film won a post-humus Best Director Oscar for Huston and a Best Supporting Actress award for his daughter Anjelica. I was drawn to the film because I was a fan of the Hustons and, most definitely of James Joyce.

John Huston was dying while working on “The Dead,” a 1987 film closely based on James Joyce’s 1914 short story in The Dubliners collection. The film won a post-humus Best Director Oscar for Huston and a Best Supporting Actress award for his daughter Anjelica. I was drawn to the film because I was a fan of the Hustons and, most definitely of James Joyce.

According to Wikipedia, “The film takes place in Dublin in 1904 at an Epiphany party hosted by two sisters and their niece. The story focuses on the academic Gabriel Conroy (Donal McCann) and his discovery of his wife Gretta’s (Anjelica Huston) memories of a deceased lover. The ensemble cast also includes Helena Carroll, Cathleen Delany, Dan O’Herlihy, Marie Kean, Donal Donnelly, Seán McClory, Frank Patterson, and Colm Meaney.”

I was happy that my favorite passage from Joyce’s story–often cited as among the most beautifully written in the English language from, perhaps the best English story story–was included in the film as a voice-over reading:

“It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

The New York Times review began:

”’ONE by one we’re all becoming shades,’ says Gabriel Conroy, looking out into Dublin’s bleak winter dawn. Gretta, the wife he loves and suddenly realizes he has never known, lies asleep on the bed nearby. His own life now seems paltry: ‘Better pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age.’

”’ONE by one we’re all becoming shades,’ says Gabriel Conroy, looking out into Dublin’s bleak winter dawn. Gretta, the wife he loves and suddenly realizes he has never known, lies asleep on the bed nearby. His own life now seems paltry: ‘Better pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age.’

“These words are spoken toward the end of ‘The Dead,’ John Huston’s magnificent adaptation of the James Joyce story that was to be the director’s last film.

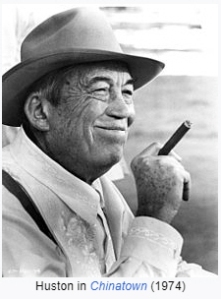

“Some men pass boldly into that other world at 17. Huston was 81 when h e died last August. He failed physically, but his talent was not only unimpaired, it was also richer, more secure and bolder than it had ever been. No other American filmmaker has ended a comparably long career on such a note of triumph.”

e died last August. He failed physically, but his talent was not only unimpaired, it was also richer, more secure and bolder than it had ever been. No other American filmmaker has ended a comparably long career on such a note of triumph.”

Pauline Kael wrote that “The announcement that John Huston was making a movie of James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ raised the question ‘Why?’ What could images do that Joyce’s words hadn’t? And wasn’t Huston pitting himself against a master who, though he was only twenty-five when he wrote the story, had given it full form? (Or nearly full—Joyce’s language gains from being read aloud.) It turns out that those who love the story needn’t have worried. Huston directed the movie, at eighty, from a wheelchair, jumping up to look through the camera, with oxygen tubes trailing from his nose to a portable generator; most of the time, he had to watch the actors on a video monitor outside the set and use a microphone to speak to the crew. Yet he went into dramatic areas that he’d never gone into before— funny, warm family scenes that might be thought completely out of his range. He seems to have brought the understanding of Joyce’s ribald humor which he gained from his knowledge of Ulysses into this earlier work; the minor characters who are shadowy on the page now have a Joycean vividness. Huston has knocked the academicism out of them and developed the undeveloped parts of the story. He’s given it a marvelous filigree that enriches the social life. And he’s done it all in a mood of tranquil exuberance as if moviemaking had become natural to him, easier than breathing.”

Wikipedia Noted: “The Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa cited The Dead as one of his 100 favorite films. The Dead received mostly positive critical reviews. The film holds a 94% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 31 reviews.”

As a work of love and a work of art, the movie wasn’t a blockbuster. But that doesn’t matter. It doesn’t need any validation other than the appreciation of those who saw it and saw it for what it was.

–Malcolm

The

The

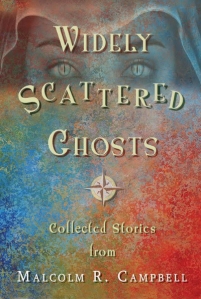

Those reading my short story “Moonlight and Ghosts” in the short story collection Widely Scattered Ghosts know that the main character takes a dim view of the state of our mental health system, in part the fact that the centers using the group home approach (that was working) gave way to the cheaper “let’s turn the mentally ill out into the community where, in reality, few people will help them.”

Those reading my short story “Moonlight and Ghosts” in the short story collection Widely Scattered Ghosts know that the main character takes a dim view of the state of our mental health system, in part the fact that the centers using the group home approach (that was working) gave way to the cheaper “let’s turn the mentally ill out into the community where, in reality, few people will help them.”

One way to add depth to a scene setting opening is through a reference to a scene in a novel, short story, or film. In my case, my opening lines were inspired by the closing lines of the James Joyce novella-length short story “The Dead” which appeared in his 1914 Dubliners collection that focussed on middle class life. I didn’t mention the link in my story, because mentioning it didn’t really fit, and because what I was thinking about was Joyce’s use of a snow metaphore in a story about the dead (which is how my character saw the existence of forgotten people in mental instutions). Here’s Joyce’s closing to “The Dead”:

One way to add depth to a scene setting opening is through a reference to a scene in a novel, short story, or film. In my case, my opening lines were inspired by the closing lines of the James Joyce novella-length short story “The Dead” which appeared in his 1914 Dubliners collection that focussed on middle class life. I didn’t mention the link in my story, because mentioning it didn’t really fit, and because what I was thinking about was Joyce’s use of a snow metaphore in a story about the dead (which is how my character saw the existence of forgotten people in mental instutions). Here’s Joyce’s closing to “The Dead”: