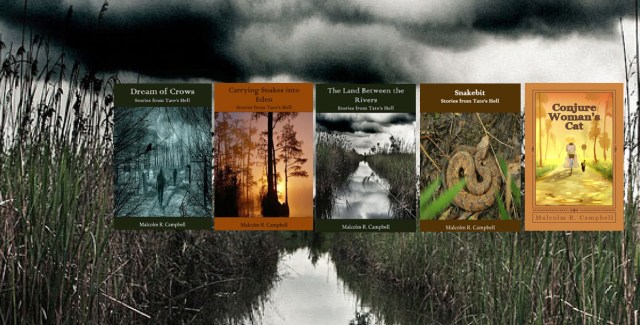

Tag: Florida

Free Kindle Short Story: “Dream of Crows”

My Kindle short “Dream of Crows” will be free on Amazon between January 21 and January 23. (The story is always free for Kindle Unlimited subscribers.)

Description: After going on a business trip to north Florida, you have strange dreams about something lurid and/or dangerous that happened in a cemetery next to Tate’s Hell Swamp. You try to remember and when you do, that’s all she wrote.

Description: After going on a business trip to north Florida, you have strange dreams about something lurid and/or dangerous that happened in a cemetery next to Tate’s Hell Swamp. You try to remember and when you do, that’s all she wrote.

Picture This: When a person has too much to drink and gets mixed up with a stunning conjure woman, exciting things can turn into dangerous things. That’s why folks need to be careful when walking into a bluesy bar where a temptress is serving drinks–and more.

Tate’s Hell Stories: This story is one of a series of books that are connected by one thing only: a forbidding swamp. The swamp, which is real, is on Florida’s Gulf Coast near the town of Carrabelle. You probably haven’t heard of the swamp or the town because they’re in what’s often called “the forgotten coast.” Those of us who grew up there hope it stays forgotten.

Obviously, this short story leans a bit into the paranormal side of things. You might also say it’s a bit experimental since you are the main character.

Have fun reading the story–if you dare.

Malcolm

I wish I’d heard the blues at the Red Bird Cafe

Just across the main east-west thoroughfare from Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida, sits the oldest black neighborhood in the state. Known as Frenchtown, the area was beginning to decline when I rode my bicycle on Macomb and Dean Streets delivering telegrams while in high school. Those older than me remembered the days when Frenchtown’s Red Bird Cafe was an important stop on the Chitlin’ Circuit, and they spoke fondly of the days when Cannonball Adderley and Ray Charles lived in the area and were famous along the streets for their music.

The yellow Western Union tag on my shirt identified me as a harbinger of death as surely as a black car in a military neighborhood. Perhaps it was that tag or perhaps it was luck, but I never ran into any trouble in Frenchtown even though most of my friends thought I was crazy to go there even though the job required it. I usually took bad news because that’s what telegrams were all about in Frenchtown. The recipients often made me open the yellow envelopes and read the messages at their front doors, and helplessly seeing their reactions and sometimes helping them compose a reply was–I think–my introduction to what it was like to feel the blues.

I wish I’d been more daring then, for I went to a Peter, Paul and Mary concert at FSU, but never went to the Red Bird other than to pedal past it on my bike. Surprisingly, I delivered–much to my embarrassment–more than one singing (usually “Happy Birthday”) telegram in Frenchtown where whole families and their neighbors gathered in the small yards to hear that poor, sweaty white boy sing. Who knows what would have happened if I’d ever had to sing such words at the front door of the Red Bird. Maybe somebody with an “axe” (guitar) would have emerged from the crowd and joined in. Never happened. But as I worked on my Conjure Woman’s Cat novella with its strong leaning toward the blues, I couldn’t help but think of Frenchtown and all the music there I never heard in the world where it lived.

If I owned a time machine, I’d get out the yellow Western Union tag that I “borrowed” from the company when I left, and I’d go back to the Red Bird and listen. In real life, all that music was at once so close and so far away.

–Malcolm

You may live in Wiregrass Country and not know it

By and large, people have forgotten wiregrass. Time was, it occupied the forest floor where longleaf pines grew. Sadly, most of the longleaf pine forest is gone as well.

The deep South is wiregrass country and for those who remember, there’s a lot of folklore in and around those old woods. “Progress” killed the longleaf pines. And, wiregrass, too. (Some people call it “Pineland Three-awn.”)

Like longleaf pines, wiregrass needs fire to prosper. Native Americans in the Florida Panhandle and south Georgia knew this and so did incoming settlers. They burned off the grass yearly. This helped the forest by clearing out all the understory clutter of brush that choked pines and pine seedlings. The grass, which returned soon after the burns, came up fresh and new and was succulent enough for cattle for a while before getting wiry and inedible.

In some ways, Smoky the Bear helped kill off our wiregrass and longleaf pine forests because he kept brainwashing us with the phrase “Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires.”

But here’s the thing: forest fires are a natural part of environmental renewal. Preventing them where they are needed harms the forest. In the 1940s, the forest service banned controlled burning and we have been paying for that mistake ever since even though the practice is now more in favor.

In Wiregrass Country, one of my favorite folklore books about the world where I grew up, Jerrilyn McGregory writes that “Wiregrass (Aristida stricta) depends on fire ecology to germinate. Its fire ecosystem created a unique set of circumstances, tied closely to a way of life…Although it was once the most significant associate in a community of species that formed the piney woods, many human inhabitants of the region have lived and died without knowing the plant.”

In Wiregrass Country, one of my favorite folklore books about the world where I grew up, Jerrilyn McGregory writes that “Wiregrass (Aristida stricta) depends on fire ecology to germinate. Its fire ecosystem created a unique set of circumstances, tied closely to a way of life…Although it was once the most significant associate in a community of species that formed the piney woods, many human inhabitants of the region have lived and died without knowing the plant.”

I grew up with wiregrass and longleaf pines and miss them. Perhaps that’s why I’m working on another novel set in “Wiregrass Country.” Maybe talking about wiregrass and pines will remind people what we once had and will help garner support for restoration efforts.

Traditions in Wiregrass Country run deep even though they often seem out of place in an increasingly “citified” world. If you grew up there, you probably ate mullet, went to peanut festivals and rattlesnake roundups, knew well the “shape note” old-style hymns of Sacred Harp music, fished or played a rousing game of fireball and loved storytellers.

If you didn’t grow up there, you missed a lot. Same goes if you grew up there in a suburban neighborhood and never ventured out into the piney woods and small towns.

Maybe it’s time to go see what it’s all about.

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell’s “Conjure Woman’s Cat” is a magical realism novella set in the wiregrass and piney woods country of the Florida Panhandle.

Malcolm R. Campbell’s “Conjure Woman’s Cat” is a magical realism novella set in the wiregrass and piney woods country of the Florida Panhandle.

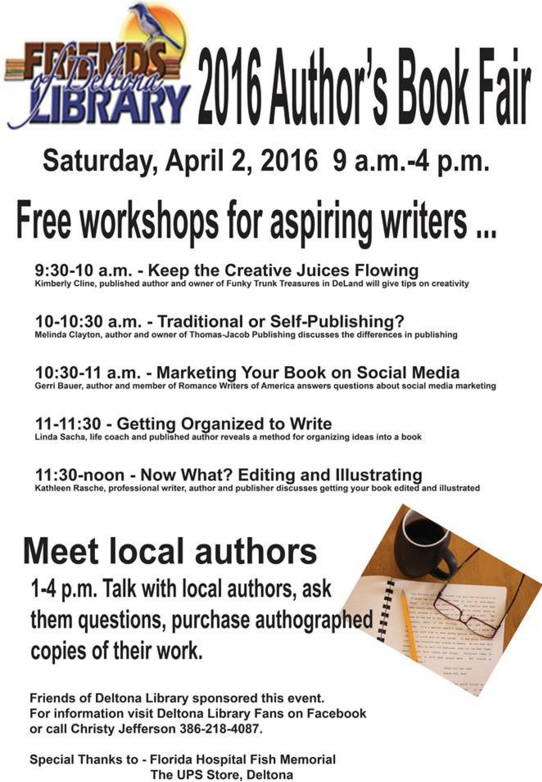

The Tate’s Hell Stories

“Who was Tate, you wonder? In Sumatra they still tell his story: how he left the frontier village at dusk a century ago with his two hunting dogs and his puppy Spark, to kill a panther that had been raiding Sumatra livestock. He carried a Long Tom shotgun and a Barlow knife, and he thought he knew where the darkening waters ran.”

– Gloria Jahoda, The Other Florida (1967)

When my 1950s-era novella Conjure Woman’s Cat came out, my publisher said that with all the book’s mentions of Tate’s Hell Swamp, how about a Kindle series of stories about the place?

Fortunately I had a bunch of things on hand, including a short story from an anthology and scene from my out-of-print novel The Seeker that just happened to be set there and in nearby Carrabelle.

I couldn’t resist the idea of taking snakes to Eden. Most of all, I enjoyed learning more about the animals and their Florida wild places environments for the folktale collection.

I’ve enjoyed coming up with three short stories and one short collection of folktales for the series.

Dream of Crows: This dark story about a businessman and a sexy conjure woman who lives next to a cemetery on the edge of Tate’s Hell is the most recent. It originally appeared in the Lascaux Prize 2014 Anthology.

Dream of Crows: This dark story about a businessman and a sexy conjure woman who lives next to a cemetery on the edge of Tate’s Hell is the most recent. It originally appeared in the Lascaux Prize 2014 Anthology.

If you’re prone to nightmares, be warned that this story is written in the second person and makes the reader the main character. Free June 24-28.

Opening lines: During the coroner’s inquest into the matter of your death, a well-meaning friend or relative will step forward with your affidavit stating that you read Dream of Crows because you saw it in your spouse’s copy of The Lascaux Review, heard several clerks at Barnes and Noble speculating about its deeper meanings, or—more likely—because you were intrigued by the probable connection between the short story and an odd string of assisted suicides in a Florida’s Tate’s Hell Swamp.

Snakebit: This slightly less dark short story came out just before Dream of Crows. Two college students fall in love while working as seasonal employees at a resort hotel in the northwest.

Snakebit: This slightly less dark short story came out just before Dream of Crows. Two college students fall in love while working as seasonal employees at a resort hotel in the northwest.

At the end of the summer, they return to their respective colleges that are far apart. When she’s assaulted on a dark street outside the college gates, she refuses to let him visit her. Finally, when he’s allowed to travel to Florida in June, he finds her much changed. The more he sees, the more he thinks he’ll have to sever the relationship. However, before he does so, the magic of Tate’s Hell intervenes.

The Dream: Then the squalling wheels in the coach’s rear truck in a tight curve fetched up the memory of the caterwauling panther of a nightmare that stalked him thirteen miles up the track. He ran between small ponds beneath a bright moon. Coowahchobee sprang out of a dark stand of hat-rack cypress and chased him through shallow water. He was trapped, suddenly, in an unyielding thicket of titi where the small white flowers exploded overhead like a dying constellation. He saw brown eyes above a deep growl that ran through his soul seconds before the claws snagged his left arm when the large cat dragged him away from the water.

Carrying Snakes Into Eden: “Eden” in this story refers to Florida’s former Garden of Eden attraction on the Apalachicola River. It’s rather a tongue in cheek story about two college students who pick up a hitchhiker with a sack of snakes he captured in Tate’s Hell. He says they’re need in the Garden of Eden.

Carrying Snakes Into Eden: “Eden” in this story refers to Florida’s former Garden of Eden attraction on the Apalachicola River. It’s rather a tongue in cheek story about two college students who pick up a hitchhiker with a sack of snakes he captured in Tate’s Hell. He says they’re need in the Garden of Eden.

The students learn that skipping church that Sunday morning may have long-term consequences.

Opening Lines: When John and I drove to Carrabelle on a gray Sunday morning for brunch with the Boynton sisters, skipping church was the least of our sins. Julie and Kathy were seniors, cheerleaders, and the most popular blondes in high school. John and I, mere juniors, wore clean sport shirts and Jade East aftershave. Brunch was canceled when the parents returned from New Orleans on Seaboard’s Gulf Wind a week early. They saved us from prospective sins of the flesh. But we weren’t home free. In fact, our transgression on that April day in 1961 was a first for the Florida Panhandle.

The Land Between the Rivers: This series of three folktales set in Tate’s Hell at the dawn of time is introduced by Eulalie, my conjure woman in the novella. They begin where the Seminole creation myth leaves off with stories about Panther, Snakebird and Bear–the first animals to walk the earth in the old legends.

The Land Between the Rivers: This series of three folktales set in Tate’s Hell at the dawn of time is introduced by Eulalie, my conjure woman in the novella. They begin where the Seminole creation myth leaves off with stories about Panther, Snakebird and Bear–the first animals to walk the earth in the old legends.

Panthers, of course, are highly endangered in Florida. When I was young, there were panthers in Tate’s Hell. Now they’re gone from the panhandle and can only be found in central and south Florida.

Openning Lines: One day when I was just a piddling kitten no bigger than a crow, I fell into Coowahchobee Creek while helping my conjure woman look for crawfish. The cold water spun me around like pinecone. I sulled up into a snarling fit three times my normal size and swatted the rocks and roots along the bank with my claws.

“Hush, little one,” Coowahchobee whispered. “Lena, look directly into Eulalie’s haint blue eyes and your thoughts will tell her you are ready to hear our stories.”

These stories all see for 99 cents and occasionally are featured free in book sales. I hope you enjoy them even if you don’t live in the Florida Panhandle.

–Malcolm

“Conjure Woman’s Cat” is available on Kindle ($2.99) and in paperback ($8.58) and, in addition to Amazon, can also be found at Powell’s, B&N, Smashwords and other online book sellers.

“Conjure Woman’s Cat” is available on Kindle ($2.99) and in paperback ($8.58) and, in addition to Amazon, can also be found at Powell’s, B&N, Smashwords and other online book sellers.

The Power of Obscure Events in Fiction

“Claude Neal was an African American farmhand living in Jackson County, Florida who was accused of raping and murdering Lola Cannady, a nineteen year old white female, just outside the town of Greenwood on October 18, 1934.” — Wikipedia

Outside of Jackson County in the Florida Panhandle, I doubt many current Florida residents are aware of the lynching of Claude Neal by a mob after he was accused of raping and killing Lola Cannady.

It was a brutal incident and became a yet another notorious example of why the country needed anti-lynching laws.

I grew up in Florida during a time when local history was taught in the schools, so I’m aware of many of the panhandle’s legends, crimes, folklore, things to do and places to see.

The old story came to light again in 2011 when the FBI said it couldn’t close the case. (There’s a link in the graphic below.) So people knew or re-remembered the case for a while. But time passes and that knowledge fades quickly.

Needless to say, I hope my recently published novella Conjure Woman’s Cat will have a wider appeal than readers who live between Tallahassee and Pensacola. So why did I mention–just in passing–an obscure event when I could have just as easily made something up?

For better or worse, here’s how a writer’s mind works when it comes to creating a fictional town in the real world:

- The description of historian Dale Cox’s book notes that this event has been called the “last public spectacle” lynching in U.S. history. Consequently, the African American characters in my 1950s-era story set in a town a few miles from where the lynching occurred would certainly know about it even though it happened 20 years earlier. To my characters, there’s not only a precedent for such violence but a chance it could happen again since the “climate” and the attitudes haven’t changed much.*

-

Picture and cutline from Explore Southern History. Places are understood by many as not only their geography but as defined in part by what has happened there. It’s hard to mention Gettysburg without thinking about the Civil War battle there. Gettysburg is shaped partly by that battle, the intervening response to that battle, and–if you like magical realism and/or the paranormal–by the psychic strength of that event. Jackson County and nearby Liberty County, Florida were what they were in the Jim Crow 1950s partly because of the violence created an nurtured by a lot of KKK activity.

-

Sometimes those obscure events come back into our consciousness again. When the characters in my fictional town fear mob violence after the rape of a local black girl by whites, it’s natural for them to think of what’s happened before. I strongly believe that authors who write about places should try to preserve the real stories–myths, legends, real events–of those places in their fiction. Even the casual mention of a real event, as opposed to a fictional event I could have easily made up, not only keeps history alive, but offers stories stronger foundations than one can get out of fabricated folklore and history.

- Mention a real event–or an existing myth–and you can enlarge your story’s impact by keying off of things readers believe–as they read your fiction–they might have heard about before; or perhaps they’ll wonder about it and Google it or otherwise read further. If you dumped all this history into your story, your research “would show,” as people say. In my case, I wasn’t writing historical fiction, much less a dramatization of the Claude Neal lynching. But, if I can tempt you to consider the very real environment in which my story was set, then the story potentially has a larger meaning than its fictional plot, theme and characters can convey.

Basically, the power of obscure events in fiction is context. The story doesn’t unfold in a vacuum but in a real place with real rivers (the Apalachicola), real foods (catfish and hush puppies), real forests (longleaf pines), real industries (turpentine) and real history.

All of those things fit hand-in-glove with the stuff the author is making up. As far as I know, the town I created (Torreya) never existed. Neither did a hoodoo woman (Eulalie), her cat (Lena) or her good friend (Willie Tate). But they are who they are in the story because of the kinds of things that happen in the place where they live.

Storytelling advice often focuses on plots and characters, and that’s not a bad part of the craft from which to begin. Writers have learned over time than modern readers won’t tolerate pages and pages of description. But readers find resonance in fully developed context: that is to say, the real in the story makes the fictional in the story seem real.

–Malcolm

* The reality of a lynching in Florida in the early 1950s was punctuated by the fact that when Ruby McCollum was accused of killing a white doctor in Live Oak, Florida in 1952, she was held in a state prison to protect her from a potential lynching had she been confined prior to trial in a local jail.

The “Conjure Woman’s Cat” giveaway continues on GoodReads until April 15th. Enter for a chance to win one of three paperback copies.

Seminole Pumpkin Fry Bread

One of the first things I learned to cook was fry bread. Didn’t take long to get it right because it has very few ingredients and is one of those foods that (like making biscuits) is done by the feel of the dough rather than slavishly measuring ingredients into a mixing bowl.

If you work the hell out of the dough, you’ll ruin it like you can when making pasta. The dough works better if you make it one day, cover it over night with tin foil (AKA aluminum foil) in the ice box (AKA fridge), and make the bread the following day.

There are a lot of variations, but pumpkin tops my list, though you can experiment with butternut squash instead of pumpkin. I like it plain, but some folks add cinnamon or nutmeg or vanilla extract (food Lord!) or even dust the tops with powdered sugar like they’re making Beignets in New Orleans (what the hell?).

If you’re using self-rising flour, then flour (about 3 cups), pumpkin (let’s say 4 cups), and sugar (a cup or less) is all it takes. With all-purpose flour, you’ll need a tablespoon of baking soda as well. And some cooking oil or lard. Pumpkins harvest in the fall, so if you have fresh, chop them up and boil it. If not, canned pumpkin works fine. (If you don’t want the pumpkin in it, use water or milk when mixing the flour. If you don’t want it sweet, leave out the sugar.)

Let it sit overnight. Don’t skip this step.

The next day, roll the dough into balls and then flatten them with your fingertips so they’re thin enough to cook all the way through before they burn on the outside. Taste the dough before you do this to see if it needs more sugar or is too sticky and needs more flour. Put the little cakes in a skillet or pan of hot oil (medium-high).

Turn them when the edges get brown. Medium brown is what you’re looking for and that usually happens when the cakes float. Drain on a paper towel. Great for snacks or to go with your dinner.

If you like pictures to go with your recipes, the Seminole Tribune has a series of what-it-ought-to-look-like pictures here.

I don’t normally talk about food on this blog, but I mentioned pumpkin fry bread a fair number of times in my 1950s-era folk magic novella Conjure Woman’s Cat and that was enough to get me addicted to it all over again. Seems like everyone in Florida made fry bread in the 1950s.

In many Indian nations, making and eating fry bread is sacred and deeply linked to the past.

–Malcolm

All three of Campbell’s “conjure and crime” novels have been collected into one e-book.

Crossings, magical and otherwise

There’s a railroad crossing on the cover of my upcoming novella Conjure Woman’s Cat because several incidents in the book occur at a crossing and crossings are associated with magic.

There’s a railroad crossing on the cover of my upcoming novella Conjure Woman’s Cat because several incidents in the book occur at a crossing and crossings are associated with magic.

The Florida Panhandle has traditionally been tied to the timber and turpentine industries. In the 1950s era when my book was set, pines, pulpwood, scraped trees with cups collecting resin for turpentine, and logging trains were common sights.

In modern times, we associate road crossings with red lights, traffic jams, hard-to-make left turns and accidents. Railroad crossings are places where drivers have to wait for trains and, by all means, stop, look and listen.

Crossings have always been associated with danger. Robberies happened there, armed men clashed there, and people got lost there.

All of this translates nicely into various forms of folk magic, including hoodoo, and in mythology. Like borders, crossroads were often considered to be uncertain places where realms, domains, countries and states of mind came together. Such places were often like oil and water in that they didn’t properly mix–“neither here nor there” folks often said. There is power at a crossroads, for good and ill.

In hoodoo, the crossroads is the place where one summons demons and bargains for skills they need: in my novella, a young girl goes to a crossing to learn how to sing the blues. “Crossing” also refers to wavy lines an X mark (or quincunx) placed on the ground where one harms or shames another person through “foot-track magic.”

Powders and liquids used to jinx the path where the victim is expected to walk are said to enter or contact that person through the soles of his feet. Folks who know conjure, watch where they walk and also carry mojo bags, charms and other items to ward off evil.

Today we use the term “street wise” to those who know what to watch out for in the inner city; I think we can safely say one needs to be equally aware in a rural area where a root doctor (conjure woman) lives.

Turpentine and pulpwood mean logging trains, a constant image in my book. People traveling the road into town see bulkhead flat cars at the railroad crossing heading for the paper mill. Where the tracks cross the road is also a tempting place to “lay a trick.”

I like the interplay of the magical and the real, and “crossings” (symbolic and real) offer a lot of “neither here nor there” kinds of places in a conjure story. A piney woods story wouldn’t be real without railroad crossings, bulkhead flat cars (typical for hauling wood) and turpentine stills.

I hope readers will enjoy the double meanings in the story as well the dangerous events that occur where one road (or railroad) crosses another road.

![]() You can read an interesting summary of crossings in hoodoo at the extensive Lucky Mojo site. (To Put on Curses, Jinxes, and Crossed Conditions, To Destroy Luck and Change Good Luck to Bad, For Revenge and Spiritual Antagonism).

You can read an interesting summary of crossings in hoodoo at the extensive Lucky Mojo site. (To Put on Curses, Jinxes, and Crossed Conditions, To Destroy Luck and Change Good Luck to Bad, For Revenge and Spiritual Antagonism).

You can read the Wikipedia overview of crossroads magic here and the post Mystery, Magic & Mayhem of the Crossroads here.

As always, I enjoy pulling the details and secrets of a place into my fiction and very much sharing the Florida world where I grew up.

Sky, from the toes up

“I thank you God for this most amazing day, for the leaping greenly spirits of trees, and for the blue dream of sky and for everything which is natural, which is infinite, which is yes.” – e. e. cummings

When I was in the first or second grade and learned that the earth revolves, I wondered why the ground did not move beneath my feet when I jumped. How perplexing; I come down just where I started, I thought.

When I was in the first or second grade and learned that the earth revolves, I wondered why the ground did not move beneath my feet when I jumped. How perplexing; I come down just where I started, I thought.

My dad explained that the atmosphere moves with the earth and, in fact, if it didn’t, there would be a substantial windstorm blowing us down around the clock.

For years, I viewed the sky as something far way, especially on clear nights when the stars—according to my observations—moved on flight paths much more distant that clouds, airplanes, or the helium balloons that escaped our grasp at the county fair.

I supposed at an early age that an ant’s view of the sky includes everything from my toes up. My feet are shadows and my hands are clouds and my head is a far planet. I believed they were misinformed and/or had poor eyesight because the sky was miles away.

Early on a Saturday morning when I was in high school, I went to Alligator Bay on the Gulf Coast south of Tallahassee, Florida, with Tommy and Jonathan for a boat ride over to Dog Island. Jonathan’s family had a speed boat anchored just off the beach near his family’s summer cottage. The faraway sky was blue and cloudless, and the water was tranquil.

After a day of swimming, snorkeling and sand-dune exploring, we headed back just as a storm began developing farther to the west. The sky grew very dark before we reached the bay sheltered by Alligator Point. The high chop of the waves slowed our progress, so the afternoon was winding down before we set the anchor and waded ashore. We were quite relieved we hadn’t swamped the boat, something we hadn’t done for a year or two.

As we stood watching the storm pass by outside the bay, the setting sun appeared low on the western horizon with one of the most spectacular golden sunsets I have ever seen. The beach, the boat, and the surf were bright orange and glowing with light. Meanwhile, the lightning from the passing storm to the south of us, was also bright orange, and it hissed as it snaked across the sky over our heads and shook the world with its hollow thunder.

We stood without saying a word, and to this day, I think those moments still represent one of the most mystical experiences I have ever had. On that golden beach just out of the storm’s reach, everything was possible and yes and hopeful and connected. “The sky is everywhere, it begins at your feet,” wrote Jandy Nelson in her young adult novel. Yes it is, and on that afternoon, it was clear to me that I stood within the sky and not below it.

–Malcolm

This post originally appeared on my Magic Moments weblog. As I get ready to shut down that blog, I thought I’d run a few of my favorite posts from the archive. Looking back on that day on the beach made it easier for me to understand a quote from “Seth” in the books by Jane Roberts: “There is no place where consciousness stops and the environment begins, or vice versa.”

On Location: the Apalachicola River

The Apalachicola River in the Florida Panhandle is created at the Georgia border by the Flint and Chattahoochee rivers and then flows 112 miles to the Gulf of Mexico. The river has been in the news in recent years as Florida, Georgia and Alabama fight over who owns the water. Atlanta takes more than its fair share, some say, starving natural areas North to South down the panhandle and, worse yet, the fragile ecosystem of Apalachicola Bay.

From the air, there are places where the river looks like a very large green snake because it twists and turns and almost coils back on itself. The ecosystems have been under stress for years. The river has been improperly dredged; the pine forests have been over logged and–when it comes to longleaf pines–poorly managed; roads to the timber have blocked natural water flows through swamps and other wetlands. The rare Florida Panther can no longer be found in the river’s watershed.

The Apalachicola River was the western boundary of my childhood, for we camped along its banks and on the barrier islands protecting the bay, sailed from its mouth to and from Alligator Point and the St. Marks River to the east, drove or walked every forest service road from Tallahassee to Tate’s Hell Forest (near the mouth of the river at Carrabelle), and experienced one of the most unique ecosystems in the country.

The Apalachicola Riverkeeper says that the river’s basin is home to 127 very rare plant and animal species along with more reptiles and amphibians than any other place in the in the northern hemisphere. The river is not only a resource many habitats, but also for kayakers, fishermen, paddle boaters, swimmers, photographers and–in the bay–a very large fishing industry.

I’ve always been rather jealous of those who knew every plant in the swamp and forest as well as those who knew how to chart river flows, analyze soil and restore forest lands. The Nature Conservancy is at work in this area, trying to undo many years of damage while protecting lands from more “development.” Since I’m not a scientist or a naturalist, I try to focus on natural resources in my fiction. It’s my way of drawing attention to the environment.

Lately, I’ve been at work on a novella set in a fictional town a few miles from the Apalachicola River in Liberty County, the Florida county with the lowest population. In many ways it’s like going home to look at these areas again and put them into stories. I recently finished reading a political thriller novel called Mercedes Wore Black (which I review here.) The main character is an environmental reporter, making the book a very strong window framing Florida’s ongoing developers vs. the environment battles.

The author of that book lived in Florida more recently than I have and as a long-time reporter, she could focus more clearly on the issues from a practical standpoint. I try to focus on the locations and make readers aware of the ecosystems’ value in the scheme of things without getting into many political rants.

Some of my poet friends write poems about the environment. Photographers are taking pictures of things the way they are while hoping they won’t become the way they were. I’m pleased at the number of groups, blogs, Facebook pages and initiatives that are campaigning for various ways to save the land before we ruin it all.

I’m not a political activist, though I’ve dabbled in it from time to time. My focus is fiction. Many of my readers’ focus is travel and outdoor recreation, often with a spiritual component. If you’re a writer, you can “go on location” in a dozen ways to pinpoint natural resources and the need to keep them natural.

There are times when I think that the land itself is an important “character” in my novels and stories. If the land draws you, then your pen, camera, blog and voice can help preserve it.

You May Also Like:

- The Nature Conservancy’s Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve

- Tate’s Hell Forerst restoration plan

- Apalachicola River Paddling Trail System

- On Location: Longleaf Pine along the Florida coast

Malcolm R. Campbell’s novel “The Seeker” is partially set in Tate’s Hell Forest, while his short stories “The Land Between the Rivers,” “Emily’s Stories,” “Cora’s Crossing” and “Moonlight and Ghosts” also have Florida settings.