“Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June 1564, following King Charles IX’s enlisting of Jean Ribault and his Huguenot settlers to stake a claim in French Florida ahead of Spain. The French colony came into conflict with the Spanish, who established St. Augustine in September 1565, and Fort Caroline was sacked by Spanish troops under Pedro Menéndez de Avilés on 20 September. The Spanish continued to occupy the site as San Mateo until 1569.” – Wikipedia

“Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June 1564, following King Charles IX’s enlisting of Jean Ribault and his Huguenot settlers to stake a claim in French Florida ahead of Spain. The French colony came into conflict with the Spanish, who established St. Augustine in September 1565, and Fort Caroline was sacked by Spanish troops under Pedro Menéndez de Avilés on 20 September. The Spanish continued to occupy the site as San Mateo until 1569.” – Wikipedia

When we moved to Tallahassee in time for me to start the first grade, the family took multiple short trips around Florida to learn about “our new state,” among them a trip to Fort Caroline. I was disappointed that the Fort was no longer there; just a memorial on or near the site where Laudonnière’s expedition probably landed.

The trip was still worthwhile, especially to me because I’d read about the French/Spanish conflict in a juvenile-level historical novel called The Flamingo Feather that was written by Kirk Munroe written in 1887. I checked the book out of my grade school or junior high school library and found it fascinating and filled with action. (I sided with the French, by the way.) In many ways, this was my introduction to the concept of the historical novel, especially one that teaches a subject about which we learned very little in school.

The trip was still worthwhile, especially to me because I’d read about the French/Spanish conflict in a juvenile-level historical novel called The Flamingo Feather that was written by Kirk Munroe written in 1887. I checked the book out of my grade school or junior high school library and found it fascinating and filled with action. (I sided with the French, by the way.) In many ways, this was my introduction to the concept of the historical novel, especially one that teaches a subject about which we learned very little in school.

If the “look inside” feature on Amazon is accurate, the book appears to be set in a small type; it also comes with a boring cover and appears to be missing the original illustrations. There is no description saying what the novel is about. Where that description would normally appear; we find this:

“This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important, and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it. This work was reproduced from the original artifact, and remains as true to the original work as possible. Therefore, you will see the original copyright references, library stamps (as most of these works have been housed in our most important libraries around the world), and other notations in the work. This work is in the public domain in the United States of America, and possibly  other nations. Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity (individual or corporate) has a copyright on the body of the work. As a reproduction of a historical artifact, this work may contain missing or blurred pages, poor pictures, errant marks, etc. Scholars believe, and we concur, that this work is important enough to be preserved, reproduced, and made generally available to the public. We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant.”

other nations. Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity (individual or corporate) has a copyright on the body of the work. As a reproduction of a historical artifact, this work may contain missing or blurred pages, poor pictures, errant marks, etc. Scholars believe, and we concur, that this work is important enough to be preserved, reproduced, and made generally available to the public. We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant.”

You can read the book free on at Lit2Go where it’s described briefly: “When Rene De Veaux’s parents die he goes to live with his uncle, who happens to be setting out on an exploration of the new world.” The book is also available on Project Gutenberg where you can read it online (with illustrations) or download it as a Kindle or EPUB file.

I’m biased in favor of the book since it’s one of the first novels I read. It’s a good story even though today’s readers will find the style and approach rather archaic.

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell writes magical realism novels set in the Florida Panhandle of the 1950s.

On Christmas night, 1951, a bomb exploded in Mims, Florida, under the home of civil rights activist and educator Harry T. Moore.

On Christmas night, 1951, a bomb exploded in Mims, Florida, under the home of civil rights activist and educator Harry T. Moore.

The novel is easy to read but the most exciting part of the caper is provided by the hurricane, and this is where we find the book’s most effective writing. A man is killed during the story, purportedly by falling tree limbs, but bookstore owner Bruce Cable of Bay Books doesn’t think so. The local police don’t seem interested, so the caper aspect of the novel begins when Bruce and his friends start trying to find out what really happened.

The novel is easy to read but the most exciting part of the caper is provided by the hurricane, and this is where we find the book’s most effective writing. A man is killed during the story, purportedly by falling tree limbs, but bookstore owner Bruce Cable of Bay Books doesn’t think so. The local police don’t seem interested, so the caper aspect of the novel begins when Bruce and his friends start trying to find out what really happened.

Lawyer and priest Cullen Post believes Quincy Miller’s 22 years in prison for a murder he did not commit represent not only a miscarriage of justice but brought additional power and financial gain to a small-town Florida sheriff and the criminals he sheltered, aided, and abetted. Proving Quincy Miller’s innocence is a tall order, perhaps impossible, especially when those who framed him want him to quietly rot in prison dead or alive.

Lawyer and priest Cullen Post believes Quincy Miller’s 22 years in prison for a murder he did not commit represent not only a miscarriage of justice but brought additional power and financial gain to a small-town Florida sheriff and the criminals he sheltered, aided, and abetted. Proving Quincy Miller’s innocence is a tall order, perhaps impossible, especially when those who framed him want him to quietly rot in prison dead or alive.

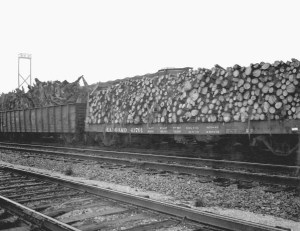

The St. Joe Paper Company in the 1950s when my novels are set, had a massive influence in the panhandle: paper mill, landholdings, a railroad called the Apalachicola Northern that carried wood products from the coastal mill to Quincy, Florida for transfer to mainline railroads. The paper company, part of a trust established by the du Pont family, still exists but focuses on commercial and residential real estate. The railroad, named the Apalachicola Northern, was referred to as the Port St. Joe Route. (It still exists as part of a conglomerate.)

The St. Joe Paper Company in the 1950s when my novels are set, had a massive influence in the panhandle: paper mill, landholdings, a railroad called the Apalachicola Northern that carried wood products from the coastal mill to Quincy, Florida for transfer to mainline railroads. The paper company, part of a trust established by the du Pont family, still exists but focuses on commercial and residential real estate. The railroad, named the Apalachicola Northern, was referred to as the Port St. Joe Route. (It still exists as part of a conglomerate.)