Man is a thinker.

He is that what he thinks.

When he thinks fire

he is fire.

When he thinks war,

he will create war.

Everything depends

if his entire imagination

will be an entire sun,

that is, that he will imagine himself completely

that what he wants.

— Paracelsus

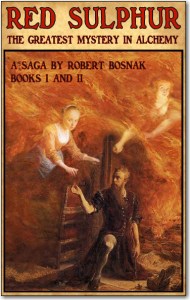

Red Sulphur: The Greatest Mystery in Alchemy [Kindle Edition], by Robert Bosnak, Red Sulphur Publications (December 8, 2014), 508pp

As I read this book, I cannot help but think of author Katherine Neville (The Eight, The Fire) who popularized the magical saga long before Dan Brown took the form to even larger audiences. I also cannot help but note that Robert Bosnak is a long-time Jungian analyst with widely-read nonfiction books to his credit who has studied alchemy for years. Jung was also a student of alchemy, seeing it as widely applicable to the understanding and development of the self. The heritage behind Red Sulphur brings great promise to this novel.

From the Publisher: It is 1666, the Year of the Beast, seen by many as the moment the Devil will appear on earth.

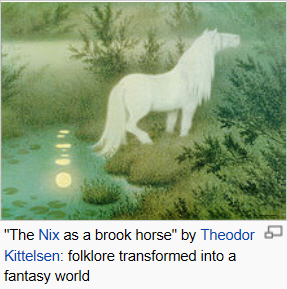

Science is in ascendance, crowding out other systems of thought. The ancient art of alchemy is in retreat. No one has been able to make the Philosophers’ Stone for over a hundred years, but many of the best minds of the age are still in a desperate search for it. Stories vividly abound how alchemists of yore had created a powerful stone of sorcery, rejuvenating all it touches — turning decrepit old lead into precious fresh gold. A universal medicine known to the alchemists by its true name: Red Sulphur.

From the Novel’s Epigraph: “This saga is based on the last verified historical reports by credible withesses about a mysterious transmutation. It follows the lives of a great alchemist and the two extraordinary women he loves. The last in the world in possession of the miraculous Red Sulphur, the source of all creative powers, they are pursued by dark forces and powerful world leaders. This is a visionary tale spanning two generations in the last days when magic was strong. It is the story of the final embers of the long gone days when the Magi could still do what we, children of science, hold to be impossible.”

Editorial Reviewer Comment: “A book both compelling and haunting. Robert Bosnak’s saga Red Sulphur traces the history of the split between alchemy and science in a tale of lust, greed and abiding passion.” – Penny Busetto:

From the author’s Amazon Page: “ROBERT BOSNAK grew up in Holland, trained in Switzerland, and has studied alchemy for over 40 years. He is a noted Jungian psychoanalyst specialized in dreaming with a practice in Los Angeles, and is the author and editor of 7 books of non-fiction in the fields of dreams, health, and creative imagination. His bestselling A Little Course in Dreams was translated into a dozen languages. He developed a method called ’embodied imagination’ used widely in psychotherapy and applied worldwide to a variety of creative endeavors. The Red Sulphur saga is his first published work of fiction. He lives in the mountains of Santa Barbara.”

You have to be an alchemist, a Jungian or a mystic to love this book. That’s the beauty of it as a saga. You don’t need footnotes; instead, you need simply to love a story. The story might change you in ways you don’t expect, but then reading always has that kind of power over those who resonate with the characters, plots and themes.

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of magical realism and contemporary fantasy novels including “The Seeker.”

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of magical realism and contemporary fantasy novels including “The Seeker.”