Scheherazade, the teller of the tales in The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, captured my imagination when I was in junior high school. The stories are fascinating. So was the idea of the narrator telling one story per night–but never quite ending it–to keep the king from killing her when a tale ends which he had threatened to do. Or perhaps it was her name that drew me in and never let me go.

Scheherazade, the teller of the tales in The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, captured my imagination when I was in junior high school. The stories are fascinating. So was the idea of the narrator telling one story per night–but never quite ending it–to keep the king from killing her when a tale ends which he had threatened to do. Or perhaps it was her name that drew me in and never let me go.

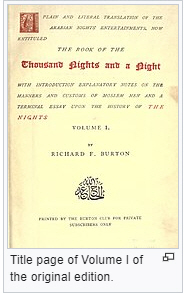

My parents are at fault because they gave me a copy of the book as a gift for Christmas or my birthday. It’s around here somewhere. Suffice it to say, it wasn’t the definitive 1880s translation from Richard Burton (1821–1890) which filled many volumes and might still be the only complete English translation.

I also had a copy of Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 symphonic suite “Scheherazade” based on the story. I had it on vinyl. It’s also around here somewhere, though I probably wore all the grooves off. My copy is older than the version shown here.

I also had a copy of Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 symphonic suite “Scheherazade” based on the story. I had it on vinyl. It’s also around here somewhere, though I probably wore all the grooves off. My copy is older than the version shown here.

I still like the stories now, many years after I first read them, and wonder how many high school and college students study the book anymore. I hope they do, for though it comes from another time, place, and culture, it presents stories that demand our attention and that keeps us reading–rather like the king who fell in love with Sheherazade (sparing her life) while she was telling her stories every night.

from the Publisher (current edition)

“THE BOOK OF THE Thousand Nights and a Night VOLUME V Translated by RICHARD F. BURTON Limited to one thousand numbered sets 1885 (London “Burton Club” edition), illustrated The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885), subtitled “A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments”, is a celebrated English language translation of “One Thousand and One Nights” (the “Arabian Nights”) – a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (8th−13th centuries) – by the British explorer and Arabist Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890). It stood as the only complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) of the “Arabian Nights” until 2008. “One Thousand and One Nights” (Arabic: كِتَاب أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة kitāb ʾalf layla wa-layla) is a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the Arabian Nights, from the first English language edition (1706), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales themselves trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folklore and literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān (Persian: هزار افسان, lit. A Thousand Tales) which in turn relied partly on Indian elements. Initial frame story of the ruler Shahryār (from Persian: شهريار, meaning “king” or “sovereign”) and his wife Scheherazade, (from Persian: شهرزاد, possibly meaning “of noble lineage”), and the framing device incorporated throughout the tales themselves. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while others begin and end of their own accord. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.”

“THE BOOK OF THE Thousand Nights and a Night VOLUME V Translated by RICHARD F. BURTON Limited to one thousand numbered sets 1885 (London “Burton Club” edition), illustrated The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885), subtitled “A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments”, is a celebrated English language translation of “One Thousand and One Nights” (the “Arabian Nights”) – a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (8th−13th centuries) – by the British explorer and Arabist Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890). It stood as the only complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) of the “Arabian Nights” until 2008. “One Thousand and One Nights” (Arabic: كِتَاب أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة kitāb ʾalf layla wa-layla) is a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the Arabian Nights, from the first English language edition (1706), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales themselves trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folklore and literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān (Persian: هزار افسان, lit. A Thousand Tales) which in turn relied partly on Indian elements. Initial frame story of the ruler Shahryār (from Persian: شهريار, meaning “king” or “sovereign”) and his wife Scheherazade, (from Persian: شهرزاد, possibly meaning “of noble lineage”), and the framing device incorporated throughout the tales themselves. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while others begin and end of their own accord. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.”

These stories took me to another world as did the music. Take a look and you might have a similar experience though not with my obsession. I do believe these stories are “must-reading” because they are a strong component of the world’s literary heritage–as are the Shakespeare plays–and demand our attention. That is to say, part of being a multi-genre, multi-cultural, reader is to dip one’s toe (if not more) into the stories spun by Scheherazade and know more of the world outside our neighborhoods.

These stories took me to another world as did the music. Take a look and you might have a similar experience though not with my obsession. I do believe these stories are “must-reading” because they are a strong component of the world’s literary heritage–as are the Shakespeare plays–and demand our attention. That is to say, part of being a multi-genre, multi-cultural, reader is to dip one’s toe (if not more) into the stories spun by Scheherazade and know more of the world outside our neighborhoods.

–Malcolm

Most of us are aware that in 2015, the Department of the Interior finally recognized “Denali” as the official name for the mountain formerly called Mount McKinley. Alaska had been calling the Peak “Denali” for forty years already. Perhaps someday the world will officially recognize the Nepalese name “Sagarmatha” as the correct name for Mount Everest (shown here).

Most of us are aware that in 2015, the Department of the Interior finally recognized “Denali” as the official name for the mountain formerly called Mount McKinley. Alaska had been calling the Peak “Denali” for forty years already. Perhaps someday the world will officially recognize the Nepalese name “Sagarmatha” as the correct name for Mount Everest (shown here). While Sir. George Everest (4 July 1790 – 1 December 1866) had more to do with Sagarmatha (Goddess of the Sky) than President McKinley had to do with Denali (as a surveyor working on the connection between Northern India and Nepal), he never saw the mountain, said the word “Everest” would be difficult for people living in the area to pronounce, and didn’t believe the mountain should carry his name.

While Sir. George Everest (4 July 1790 – 1 December 1866) had more to do with Sagarmatha (Goddess of the Sky) than President McKinley had to do with Denali (as a surveyor working on the connection between Northern India and Nepal), he never saw the mountain, said the word “Everest” would be difficult for people living in the area to pronounce, and didn’t believe the mountain should carry his name. K2 in the Karakoram range, while not quite as tall as Everest, is a more difficult climb and, as such, is often called the “Savage Mountain.” Estimates are that one person dies for every four who summit the mountain. It used to be referred to as “Godwin-Austen after the English surveyor. None of the possible local names seems to stand out, but “Masherbrum” or “Chogori” might one day be considered as more appropriate.

K2 in the Karakoram range, while not quite as tall as Everest, is a more difficult climb and, as such, is often called the “Savage Mountain.” Estimates are that one person dies for every four who summit the mountain. It used to be referred to as “Godwin-Austen after the English surveyor. None of the possible local names seems to stand out, but “Masherbrum” or “Chogori” might one day be considered as more appropriate.

This statement, which is inscribed at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi is said to have originated with Thales of Miletus (c. 626/623 – c. 548/545 BC) who was purportedly one of the “Seven Sages” who served Apollo. He is credited with being the first philosopher to rely on natural science rather than myths and legends to explain ourselves and our world. His interests ranged from math to astronomy to engineering to meteorology.

This statement, which is inscribed at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi is said to have originated with Thales of Miletus (c. 626/623 – c. 548/545 BC) who was purportedly one of the “Seven Sages” who served Apollo. He is credited with being the first philosopher to rely on natural science rather than myths and legends to explain ourselves and our world. His interests ranged from math to astronomy to engineering to meteorology. Thales thought “all things are full of gods”, i.e. lodestones had souls, because iron is attracted to them (by the force of magnetism). The same applied to amber for its capacity to generate static electricity. The reasoning for such hylozoism or organicism seems to be if something moved, then it was alive, and if it was alive, then it must have a soul.

Thales thought “all things are full of gods”, i.e. lodestones had souls, because iron is attracted to them (by the force of magnetism). The same applied to amber for its capacity to generate static electricity. The reasoning for such hylozoism or organicism seems to be if something moved, then it was alive, and if it was alive, then it must have a soul. In a recent episode of “The Curse of Oak Island,” a core drilling machine brought up a large piece of wood that team members said looked like it had been shaped by an adze. I was amused to see a little graphic and description of an adze as though the tool isn’t commonly known. Okay, if you were born yesterday or a few days before, you probably haven’t been allowed to use an adze. They are not as common as they were when I was young, so maybe you see “adze” as a handy word or use in a crossword puzzle or a scrabble game.

In a recent episode of “The Curse of Oak Island,” a core drilling machine brought up a large piece of wood that team members said looked like it had been shaped by an adze. I was amused to see a little graphic and description of an adze as though the tool isn’t commonly known. Okay, if you were born yesterday or a few days before, you probably haven’t been allowed to use an adze. They are not as common as they were when I was young, so maybe you see “adze” as a handy word or use in a crossword puzzle or a scrabble game. When my brothers and I were little, my grandfather made things out of wood, so we were used to well-tended tools that could be found on a farm or in any woodworking operation. I’m happy to see that you can still buy an adze at Home Depot even though they are calling it a “forged hoe” though it appears when I search for “Adze.”

When my brothers and I were little, my grandfather made things out of wood, so we were used to well-tended tools that could be found on a farm or in any woodworking operation. I’m happy to see that you can still buy an adze at Home Depot even though they are calling it a “forged hoe” though it appears when I search for “Adze.” If you’re a woman, you’re probably thinking, “Of course you don’t, you subhuman ape.”

If you’re a woman, you’re probably thinking, “Of course you don’t, you subhuman ape.” Once upon a time, when I was starting to take my curiosity about esoteric subjects seriously, I read Wisdom of the Mystic Masters and other books by Rosicrucian author Joseph Weed. As a Rosicrucian, Weed was no doubt aware of the fact that the road to mastery is a long road. So, in looking back on these books, I’m surprised at how they were so blatantly oversold (this reminds me of The Secret) in that they implied all you had to do was read a popular account of ancient lore and soon thereafter you would become all-powerful and quasi-divine. Like The Secret, these books came and went quickly because–while there was truth in them–it could not be learned and perfected during the halftime show of the football game that had taken over the living room’s TV set.

Once upon a time, when I was starting to take my curiosity about esoteric subjects seriously, I read Wisdom of the Mystic Masters and other books by Rosicrucian author Joseph Weed. As a Rosicrucian, Weed was no doubt aware of the fact that the road to mastery is a long road. So, in looking back on these books, I’m surprised at how they were so blatantly oversold (this reminds me of The Secret) in that they implied all you had to do was read a popular account of ancient lore and soon thereafter you would become all-powerful and quasi-divine. Like The Secret, these books came and went quickly because–while there was truth in them–it could not be learned and perfected during the halftime show of the football game that had taken over the living room’s TV set. If you look closely at what these hyped books offer, it’s very similar to what James Allen wrote years ago in his wonderful 1903 book As a Man Thinketh. My father had this book on the family’s shelves and I read it long before I’d ever heard of Weed. From the book of Proverbs. Chapter 23, it is written, “As a man thinketh in his heart, so is he.” In my view, this is all we need to know. No hype is needed.

If you look closely at what these hyped books offer, it’s very similar to what James Allen wrote years ago in his wonderful 1903 book As a Man Thinketh. My father had this book on the family’s shelves and I read it long before I’d ever heard of Weed. From the book of Proverbs. Chapter 23, it is written, “As a man thinketh in his heart, so is he.” In my view, this is all we need to know. No hype is needed. infant mother Katheryn in her arms. We can see the side of the house, a shade tree, and in the background, a steam tractor. I like Edyth’s no-nonsense expression.

infant mother Katheryn in her arms. We can see the side of the house, a shade tree, and in the background, a steam tractor. I like Edyth’s no-nonsense expression.

She appeared as head nurse Dixie McCall throughout the entire 122-episode run of the action-adventure drama “Emergency!” from 1972 to 1977. The series focuses on the paramedics, firemen, and hospital support staff, showing (I think) a more accurate look at firefighting techniques than shows like “Chicago Fire.” London’s second husband Bobby Troup (to her right in the photo) was also in the cast. The show was produced by her first husband Jack Webb. Like London, Troup came from the music business.

She appeared as head nurse Dixie McCall throughout the entire 122-episode run of the action-adventure drama “Emergency!” from 1972 to 1977. The series focuses on the paramedics, firemen, and hospital support staff, showing (I think) a more accurate look at firefighting techniques than shows like “Chicago Fire.” London’s second husband Bobby Troup (to her right in the photo) was also in the cast. The show was produced by her first husband Jack Webb. Like London, Troup came from the music business.