Since my ancestry goes back to the Scottish Highlands, I usually notice how the characters’ language is portrayed in novels. Going back in time, Highlanders spoke Scots Gaelic (Gàidhlig). Or, they spoke Highland English. Sad to say, Gàidhlig has fewer and fewer native speakers every year, though I do hear of attempts to keep the language alive, one say being–as Wikipedia describes it–“Gaelic-medium education (G.M.E. or GME; Scottish Gaelic: Foghlam tro Mheadhan na Gàidhlig, FTMG) is a form of education in Scotland that allows pupils to be taught primarily through the medium of Scottish Gaelic, with English being taught as the secondary language.”

Since my ancestry goes back to the Scottish Highlands, I usually notice how the characters’ language is portrayed in novels. Going back in time, Highlanders spoke Scots Gaelic (Gàidhlig). Or, they spoke Highland English. Sad to say, Gàidhlig has fewer and fewer native speakers every year, though I do hear of attempts to keep the language alive, one say being–as Wikipedia describes it–“Gaelic-medium education (G.M.E. or GME; Scottish Gaelic: Foghlam tro Mheadhan na Gàidhlig, FTMG) is a form of education in Scotland that allows pupils to be taught primarily through the medium of Scottish Gaelic, with English being taught as the secondary language.”

The Scots that most Americans believe is Scots is lowland Scots or Lallans. So it is that novelists writing about the era of Scotland’s clans use words based on Lallans. To my ear, this is as absurd as representing all Americans by the English spoken in Georgia even though the characters in the novel live in, say–Maine. Think of your favorite novel set in one of the New England states with the characters speaking with a strong Southern Dialect.

That sounds wrong because it is wrong. That’s the reaction I have to American novelists featuring Highlander characters speaking lowland Scots. A little research would tell the author how absurd this is. What Highlanders spoke can be found quickly on Wikipedia: “Highland English (Scots: Hieland Inglis) is the variety of Scottish English spoken by many in the Scottish Highlands and the Hebrides. It is more strongly influenced by Gaelic than other forms of Scottish English.”

I suppose one can say that American authors are more accustomed to the words derived from Lallans or Broad Scots, so they believe using the words that Highlanders really spoke will sound wrong to their readers if they used Highland English.

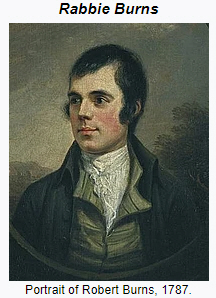

A note at the beginning of the novel would clarify why the novel’s characters from the Highlands don’t sound like Robert Burns’ poetry.

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton, (Brainston Moor[4]) was a battle fought on 9 September 1513 during the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, resulting in an English victory. The battle was fought near Branxton in the county of Northumberland in northern England, between an invading Scots army under King James IV and an English army commanded by the Earl of Surrey.[5] In terms of troop numbers, it was the largest battle fought between the two kingdoms. – Wikipedia

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton, (Brainston Moor[4]) was a battle fought on 9 September 1513 during the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, resulting in an English victory. The battle was fought near Branxton in the county of Northumberland in northern England, between an invading Scots army under King James IV and an English army commanded by the Earl of Surrey.[5] In terms of troop numbers, it was the largest battle fought between the two kingdoms. – Wikipedia

I take comfort in this old song, perhaps from my Scots heritage, perhaps from the sweet sentiments set down by Rabbie Burns in 1788. When I think of him, I am saddened by the fact he was only with us for 37 years. But what a great influence he was.

I take comfort in this old song, perhaps from my Scots heritage, perhaps from the sweet sentiments set down by Rabbie Burns in 1788. When I think of him, I am saddened by the fact he was only with us for 37 years. But what a great influence he was.