“As the Railroad marched thus rapidly across the broad Continent of plain and mountain, there was improvised a rough and temporary town at its every public stopping-place. As this was changed every thirty or forty days, these settlements were of the most perishable materials,— canvas tents, plain board shanties, and turf hovels,—pulled down and sent forward for a new career, or deserted as worthless, at every grand movement of the Railroad company. Only a small proportion of their populations had aught to do with the road or any legitimate occupation. Most were the hangers-on around the disbursements of such a gigantic work, catching the drippings from the feast in any and every form that it was possible to reach them. Restaurant and saloon keepers, gamblers, desperadoes of every grade, the vilest of men and of women made up this ‘Hell on Wheels,’ as it was most aptly termed.” – Samuel Bowles, Our New West, 1869.

The towns, which followed the Union Pacific Railroad’s portion of the Transcontinental Railroad through Nebraska and Wyoming, tended to pop up out of nowhere near the end of track to meet the primary needs of hard-working men setting down the track: booze, prostitutes, and gambling. On a more wholesome note there was usually music and dancing and, when a larger settlement was near, a few shops and maybe a church. Generally speaking, there was only one murder per night.

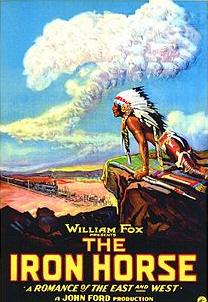

These towns were portrayed in the 1924 silent film by John Ford called “The Iron Horse,” and later in the “Hell on Wheels” TV series aired between 2011 and 2016 on AMC. These towns did not appear on the Central Pacific section of the road out of Sacramento because that line employed a large number of Chinese workers who found nothing attractive in sex, gambling, and whiskey. Frankly, these towns remind me of certain sections of the liberty ports I saw in the Navy in Japan, Hong Kong, and The Philippines.

These towns were portrayed in the 1924 silent film by John Ford called “The Iron Horse,” and later in the “Hell on Wheels” TV series aired between 2011 and 2016 on AMC. These towns did not appear on the Central Pacific section of the road out of Sacramento because that line employed a large number of Chinese workers who found nothing attractive in sex, gambling, and whiskey. Frankly, these towns remind me of certain sections of the liberty ports I saw in the Navy in Japan, Hong Kong, and The Philippines.

The Union Pacific had more than it could handle in surveying, grading, and putting down rail to bother much with the Hell on Wheels towns, though as Stephen E. Ambrose notes in Nothing Like it in the World (about the creation of the railroad between 1863 and 1869), on at least one occasion the bosses went into a Hell of Wheels town and blasted it to hell. This victory was short-lived.

According to PBS “American Experience,” “The most striking feature of these insurgent colonies was their portability. As winter thawed, and the railroaders built toward new towns, agents of vice or enterprise could simply pack up their wares, dismantle their shacks, and follow along on the newly-laid track.”

According to PBS “American Experience,” “The most striking feature of these insurgent colonies was their portability. As winter thawed, and the railroaders built toward new towns, agents of vice or enterprise could simply pack up their wares, dismantle their shacks, and follow along on the newly-laid track.”

According to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, “The first “Hell on Wheels” town began near Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory, in August 1866, when the Union Pacific line met Dobeytown, a settlement that existed to provide for the soldiers’ more earthy needs. Fort Kearny (later just Kearney) and North Platte, Nebraska; Julesburg, Colorado; Cheyenne, Laramie, Green River City, and Benton, Wyoming; and Bear River City and Corrine, Utah, were among the primary towns.”

Whether these places were heaven or hell depended on one’s perspective. If heaven, then a few murders were a small price to pay for everything you wanted after pounding spikes all day while fighting off Indians.

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of “Conjure Woman’s Cat,” the first novel in the Florida Folk Magic Series.

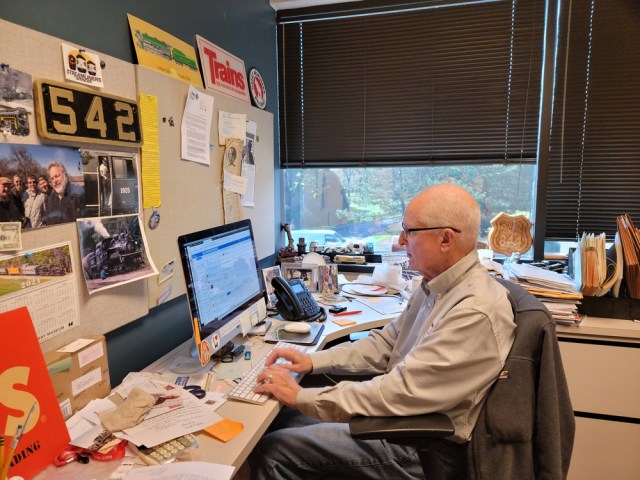

Wrinn at the Trains “81 for 81” event at the Nevada Northern Railway Museum in October 2021. Under his editorship, the magazine broadened its scope to include events like photo charters. (Cate Kratville-Wrinn)

Wrinn at the Trains “81 for 81” event at the Nevada Northern Railway Museum in October 2021. Under his editorship, the magazine broadened its scope to include events like photo charters. (Cate Kratville-Wrinn)