While serving as the chairman of my town’s Historic Preservation Commission (HPC), I heard more than my share of gripes about the taxpayer costs of city budget items that were often labeled as “fluff” during difficult economic times. City parks, historic districts, entry-road signs, green space and related tree canopy programs, and National Register of Historic Places districts were on most people’s hit lists.

While serving as the chairman of my town’s Historic Preservation Commission (HPC), I heard more than my share of gripes about the taxpayer costs of city budget items that were often labeled as “fluff” during difficult economic times. City parks, historic districts, entry-road signs, green space and related tree canopy programs, and National Register of Historic Places districts were on most people’s hit lists.

The City Parks Alliance, for example, says on its home page that “Urban parks are dynamic institutions that play a vital, but not fully appreciated or understood role in the social, economic and physical well-being of America’s urban areas and its residents.” This is a good place to start. But, when taxes, city/federal budgets and the not-so-deep pockets of residents come together, it helps to have some dollar values to assign to the catch phrases.

Even though my love of parks includes environmental concerns, habitat protection, fresh air and recreation, such “fuzzy aesthetics” as these don’t wash during a confrontational city council budget meeting. Looking at the skimpy budgetary support of our National Parks system coming out of Washington, things that are good to do for their own sake don’t get much attention in Congress either.

Economic Value – real estate, jobs, tourism

Locally, the HPC tried to stress the economic value of city parks, a value that typically exceeded the cost of maintaining the parks when viewed separately from recreational programs. In promoting economic returns, we were on the same page as the Chamber of Commerce, a group that knows the importance of such things as parks, green space, and historic preservation to corporations and individuals contemplating a move to a new city.

Locally, the HPC tried to stress the economic value of city parks, a value that typically exceeded the cost of maintaining the parks when viewed separately from recreational programs. In promoting economic returns, we were on the same page as the Chamber of Commerce, a group that knows the importance of such things as parks, green space, and historic preservation to corporations and individuals contemplating a move to a new city.

Historic districts, like museums and other cultural tourism attractions not only attract people (who make purchases throughout a city), but also create a level of interest that—according to studies—is higher than other vacation/business travel. While national parks and other wilderness areas with a lot to see tend to draw people who stay longer, the same is true for sites and attractions focusing on culture and history. Visitors to such sites stay longer and spend more than the average tourist.

Likewise, many studies have shown that the value of houses near city parks tends to be higher than the value of similar homes in other neighborhoods. While it’s easy to point fingers at the costs of maintaining a city park, their impact on real estate values is often overlooked when budgets and taxes are under scrutiny.

While city parks rated as excellent can increase the property values of nearby homes as much as 15%, the Trust for Public Land, in “Measuring the Economic Value of a City Park System” (PDF link) takes a more conservative approach to account for those parks rated as problematic: “Once determined, the total assessed value of properties near parks is multiplied by 5 percent and then by the tax rate, yielding the increase in tax dollars attributable to park proximity.”

Regional Impact of a National Park

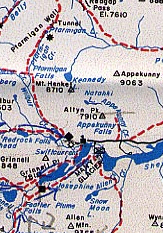

Last month, Glacier National Park released information that demonstrates the economic importance of a major tourist attraction. According to an NPS report for 2010, two million visitors came to the park, spending $10 million and supporting 1,695 local jobs.

Last month, Glacier National Park released information that demonstrates the economic importance of a major tourist attraction. According to an NPS report for 2010, two million visitors came to the park, spending $10 million and supporting 1,695 local jobs.

“Glacier National Park has historically been an economic driver in the state,” said Glacier National Park Superintendent Chas Cartwright. “This report shows the value that the many goods and services provided by local businesses are to the park visitor, as well as employment opportunities for the area.” Click on economic benefits here to download the report itself.

Personally, the value of parks to me cannot be expressed in economic terms. Yet I’m realistic enough to know that people coping with stretched-to-the-limit household budgets need to see some real dollar values attached to local and national governmental expenses before they “buy in” to the value of parks.

The Trust of Public Land, City Parks Alliance, National Park Service, and your state’s Department of Natural Resources are good places to track down information that may help win over the homeowner next door who sees nothing but red in city, state and national green spaces.

This free 48-page PDF about Glacier’s history, personalities, facilities, plants and animals can be downloaded from the Vanilla Heart Publishing page at Payloadz.

This free 48-page PDF about Glacier’s history, personalities, facilities, plants and animals can be downloaded from the Vanilla Heart Publishing page at Payloadz.