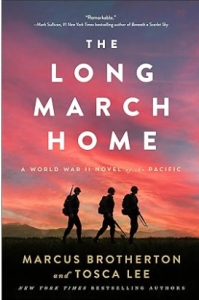

Recent winner of the International Book Award in Historical Fiction, The Long March Home was released in May of 2023. The paperback edition came out in October.

From the Publisher

J immy Propfield joined the army for two reasons: to get out of Mobile, Alabama, with his best friends Hank and Billy and to forget his high school sweetheart, Claire.

immy Propfield joined the army for two reasons: to get out of Mobile, Alabama, with his best friends Hank and Billy and to forget his high school sweetheart, Claire.

Life in the Philippines seems like paradise–until the morning of December 8, 1941, when news comes from Manila: Imperial Japan has bombed Pearl Harbor. Within hours, the teenage friends are plunged into war as enemy warplanes attack Luzon, beginning a battle for control of the Pacific Theater that will culminate with a last stand on the Bataan Peninsula and end with the largest surrender of American troops in history.

What follows will become known as one of the worst atrocities in modern warfare: the Bataan Death March. With no hope of rescue, the three friends vow to make it back home together. But the ordeal is only the beginning of their nearly four-year fight to survive.

Inspired by true stories, The Long March Home is a gripping coming-of-age tale of friendship, sacrifice, and the power of unrelenting hope.

From Publishers Weekly

“Brotherton and Lee masterfully capture what it was like for soldiers to face war’s atrocities, as well as the heartbreak of those waiting for them back home. This is a winner. ”

–Malcolm

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of the Vietnam War novel “At Sea.”

Malcolm R. Campbell is the author of the Vietnam War novel “At Sea.”

In “Castle Keep,” a rag-tag group of American soldiers is assigned to a remote Belgium castle during World War II ostensibly to protect the artwork there. With little to do, the soldiers develop their own hobbies and relationships with townspeople as though they’re all on extended leave. According to Wikipedia, “The American soldiers are happy to enjoy a respite from combat while being surrounded by unimaginable antique luxury, however, their days of leisure and peace almost undermine the very reality and the ugliness of the war itself. There is also a recurring theme of eternal recurrence, as one soldier drunkenly ponders out loud that maybe he’s “been here before”. And, although the men are eager to sit out the war that they feel will soon end, there is a sense of foreboding, a feeling of inevitability of what will eventually transpire.”

In “Castle Keep,” a rag-tag group of American soldiers is assigned to a remote Belgium castle during World War II ostensibly to protect the artwork there. With little to do, the soldiers develop their own hobbies and relationships with townspeople as though they’re all on extended leave. According to Wikipedia, “The American soldiers are happy to enjoy a respite from combat while being surrounded by unimaginable antique luxury, however, their days of leisure and peace almost undermine the very reality and the ugliness of the war itself. There is also a recurring theme of eternal recurrence, as one soldier drunkenly ponders out loud that maybe he’s “been here before”. And, although the men are eager to sit out the war that they feel will soon end, there is a sense of foreboding, a feeling of inevitability of what will eventually transpire.”

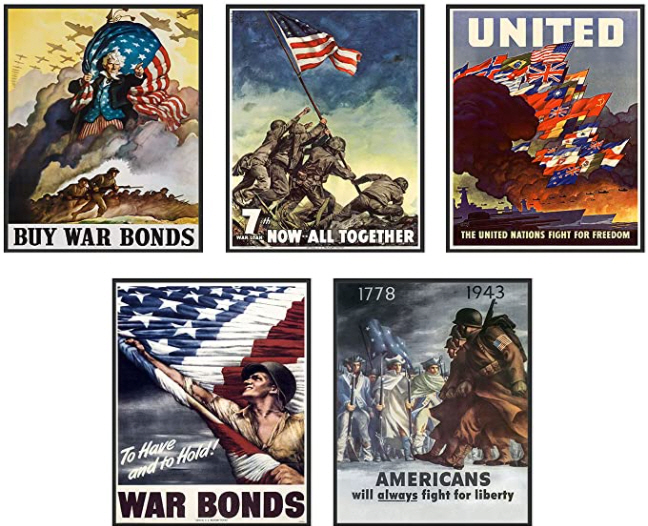

Naturally, these novels are inspired by a minority of the people living in occupied countries. Even so, the dedication of those “fighting” or fighting against the Nazis is impressive. I couldn’t help but wonder if the U.S. would have such dedicated resistance fighters if it were overrun.

Naturally, these novels are inspired by a minority of the people living in occupied countries. Even so, the dedication of those “fighting” or fighting against the Nazis is impressive. I couldn’t help but wonder if the U.S. would have such dedicated resistance fighters if it were overrun.

The cans rolling out of a machine gun like spent shell casings, while probably not an accurate portrayal of how the cans were used, pretty much dimisses the toilet idea.

The cans rolling out of a machine gun like spent shell casings, while probably not an accurate portrayal of how the cans were used, pretty much dimisses the toilet idea.

![At Sea by [Malcolm R. Campbell]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51PZZU0z4JL.jpg)

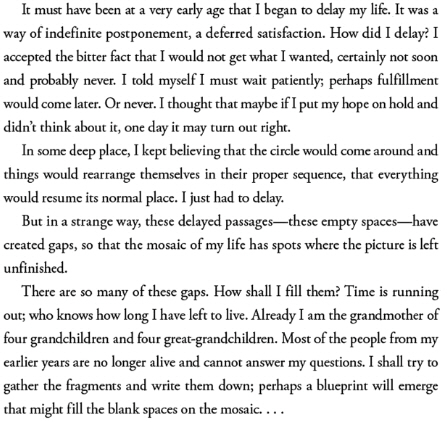

It’s a breath of fresh air at a time when for reasons I cannot comprehend anti-Semitism is rearing its polluted self around the world along with the equally bankrupt white supremacists. And then, my generation was born in the shadow of World War II and that’s had a life-long effect on us.

It’s a breath of fresh air at a time when for reasons I cannot comprehend anti-Semitism is rearing its polluted self around the world along with the equally bankrupt white supremacists. And then, my generation was born in the shadow of World War II and that’s had a life-long effect on us.