“The 1996 Mount Everest disaster occurred on 10–11 May 1996 when eight climbers caught in a blizzard died on Mount Everest while attempting to descend from the summit. Over the entire season, 12 people died trying to reach the summit, making it the deadliest season on Mount Everest at the time and the third deadliest after the 22 fatalities resulting from avalanches caused by the April 2015 Nepal earthquake and the 16 fatalities of the 2014 Mount Everest avalanche. The 1996 disaster received widespread publicity and raised questions about the commercialization of Everest.” Wikipedia

“The 1996 Mount Everest disaster occurred on 10–11 May 1996 when eight climbers caught in a blizzard died on Mount Everest while attempting to descend from the summit. Over the entire season, 12 people died trying to reach the summit, making it the deadliest season on Mount Everest at the time and the third deadliest after the 22 fatalities resulting from avalanches caused by the April 2015 Nepal earthquake and the 16 fatalities of the 2014 Mount Everest avalanche. The 1996 disaster received widespread publicity and raised questions about the commercialization of Everest.” Wikipedia

In 2023, 17 climbers died on Mt. Everest, eleven died in 2019, and eight died in 1996. Jon Krakauer wrote the book about the 1996 season, his first time on the mountain as a successful climber and a reporter.

In 2023, 17 climbers died on Mt. Everest, eleven died in 2019, and eight died in 1996. Jon Krakauer wrote the book about the 1996 season, his first time on the mountain as a successful climber and a reporter.

“Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster is a 1997 bestselling nonfiction book written by Jon Krakauer. It details Krakauer’s experience in the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, in which eight climbers were killed and several others were stranded by a storm. Krakauer’s expedition was led by guide Rob Hall. Other groups were trying to summit on the same day, including one led by Scott Fischer, whose guiding agency, Mountain Madness, was perceived as a competitor to Hall’s agency, Adventure Consultants.” – Wikipedia

“Despite being nearly 800 feet shorter than Mount Everest, K2 is a more deadly mountain. Mountaineer Jake Meyer told Insider several critical factors contribute to making K2 so dangerous. On K2, mountaineers face constant 45-degree-angle climbs, no matter the route they take, he said.” Wikipedia.

Krakauer had criticisms the book, but I believe in it was as accurate as he could make it though climbers who did not come off too good slammed the book.

–Malcolm

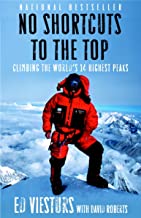

Most of us are aware that in 2015, the Department of the Interior finally recognized “Denali” as the official name for the mountain formerly called Mount McKinley. Alaska had been calling the Peak “Denali” for forty years already. Perhaps someday the world will officially recognize the Nepalese name “Sagarmatha” as the correct name for Mount Everest (shown here).

Most of us are aware that in 2015, the Department of the Interior finally recognized “Denali” as the official name for the mountain formerly called Mount McKinley. Alaska had been calling the Peak “Denali” for forty years already. Perhaps someday the world will officially recognize the Nepalese name “Sagarmatha” as the correct name for Mount Everest (shown here). While Sir. George Everest (4 July 1790 – 1 December 1866) had more to do with Sagarmatha (Goddess of the Sky) than President McKinley had to do with Denali (as a surveyor working on the connection between Northern India and Nepal), he never saw the mountain, said the word “Everest” would be difficult for people living in the area to pronounce, and didn’t believe the mountain should carry his name.

While Sir. George Everest (4 July 1790 – 1 December 1866) had more to do with Sagarmatha (Goddess of the Sky) than President McKinley had to do with Denali (as a surveyor working on the connection between Northern India and Nepal), he never saw the mountain, said the word “Everest” would be difficult for people living in the area to pronounce, and didn’t believe the mountain should carry his name. K2 in the Karakoram range, while not quite as tall as Everest, is a more difficult climb and, as such, is often called the “Savage Mountain.” Estimates are that one person dies for every four who summit the mountain. It used to be referred to as “Godwin-Austen after the English surveyor. None of the possible local names seems to stand out, but “Masherbrum” or “Chogori” might one day be considered as more appropriate.

K2 in the Karakoram range, while not quite as tall as Everest, is a more difficult climb and, as such, is often called the “Savage Mountain.” Estimates are that one person dies for every four who summit the mountain. It used to be referred to as “Godwin-Austen after the English surveyor. None of the possible local names seems to stand out, but “Masherbrum” or “Chogori” might one day be considered as more appropriate. I started reading accounts of mountain ascents and attempted ascents when I was in junior high because my father, who climbed mountains in college as I did later, had most of the classic accounts. My target peak was K2, the second-highest mountain in the world, and considered more difficult than Everest. The fatality rate on that peak is about 25%.

I started reading accounts of mountain ascents and attempted ascents when I was in junior high because my father, who climbed mountains in college as I did later, had most of the classic accounts. My target peak was K2, the second-highest mountain in the world, and considered more difficult than Everest. The fatality rate on that peak is about 25%.