Surprisingly, black ops novels give me a sense of closure in a world where’s little closure. Another pacifist friend and I discovered that we both watched the TV show “24” because, while “real life” often made us feel powerless in the face of all the issues with seemingly no answers or bad answers, Jack Bauer’s actions on the show brought us a feeling that sometimes bad guys are caught and threats are neutralized.

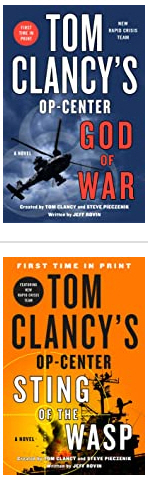

I feel the same way when I’m reading “Tom Clancy,” James Patterson, and other series in which the good guys see a threat, analyze it, and then put a stop to it. Like Jack Bauer, these good guys operate in groups that are out from under any umbrella of legalities that (as they say) “hampers” black ops.

I feel the same way when I’m reading “Tom Clancy,” James Patterson, and other series in which the good guys see a threat, analyze it, and then put a stop to it. Like Jack Bauer, these good guys operate in groups that are out from under any umbrella of legalities that (as they say) “hampers” black ops.

What bothers me, though, is how cheap life seems to be in these books. If you watched “24” you know there were car chases in which dozens of vehicles (driven by every day innocent people) were shown blowing up, turning over, falling off bridges, etc. in the background. Any police force conducting that kind of chase in “real life” would be on the carpet in minutes. But it “24” those people are collateral damage and (apparently) not so bad a price to play for Bauer catching a notorious bad guy.

While black ops novels seldom have those signature car chases that have been popular in the James Bond movies, a lot of cardboard characters always get blown away with little notice or regret en route to “a more-important goal.”

I’m sure ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and other terrorist groups see mass numbers of civilian casualties as a sign of success. Fortunately, the good guys in over-the-top novels, movies, and TV shows aren’t trying to create massive civilian casualties. In fact, in these stories, most of the cardboard characters killed are bad guys with no names who stepped ou from behind a building with blazing Kalashnikovs and got taken out by the good guys. No harm, no foul, right?

Perhaps bad guys and good guys really feel this way in “real life,” and by that I mean, operations that fall into the category of black ops rather than war. If so, this bothers me more than the deaths in fiction; with fiction, I have plausible deniability since I know none of those deaths really happened.

In “real life,” I’m against black ops, but that doesn’t mean that novels about black ops aren’t serving as addictive painkillers against the insanity of the world.

Malcolm R.. Campbell is the author of “Conjure Woman’s Cat,” “Eulalie and Washerwoman,” “Lena,” “Special Investigative Reporter,” and “Sarabande.”

Thanks to all of you who have been posting reviews on

Thanks to all of you who have been posting reviews on

I might have told this story here before. If so, bear with me. When the TV program “24” was running, a friend of mine and I realized that while we both have non-violent and anti-break-the-rules philosophies about police work and spy work, we puzzled out why we watched that series without fail. We decided that it was because the show brought us closure. That is to say, things got done, the bad guys went to jail, and the good guys (i.e., most of the population) weren’t made to sit in limbo waiting for government red tape and partisan politics to finally fix a problem.

I might have told this story here before. If so, bear with me. When the TV program “24” was running, a friend of mine and I realized that while we both have non-violent and anti-break-the-rules philosophies about police work and spy work, we puzzled out why we watched that series without fail. We decided that it was because the show brought us closure. That is to say, things got done, the bad guys went to jail, and the good guys (i.e., most of the population) weren’t made to sit in limbo waiting for government red tape and partisan politics to finally fix a problem. My latest book

My latest book

I’d be earning a living with my words even though it wouldn’t be James Patterson, Dan Brown or Nora Roberts kind of money. Since I write contemporary fantasy and magical realism, it’s a paradox that the money I did make from writing came from writing computer documentation and help files. I can be intensely logical when I want to, so my user manuals were always well thought of.

I’d be earning a living with my words even though it wouldn’t be James Patterson, Dan Brown or Nora Roberts kind of money. Since I write contemporary fantasy and magical realism, it’s a paradox that the money I did make from writing came from writing computer documentation and help files. I can be intensely logical when I want to, so my user manuals were always well thought of.