And why not? The feds are already sticking their noses into a lot of stuff that isn’t the government’s business. And if Congress were fair about the matter, it wouldn’t force everyone to churn out books like James Patterson who, as we all know, has a truckload of co-authors except on his Alex Cross novels.

Since the idea for this legislation is mine, I get to choose the authors: they would include Mark Helprin, Erin Morgenstern, Susanna Clarke, and Donna Tartt. Oh shoot, Clarke has chronic fatigue syndrome, so we can’t put her on the list. We want to, but we shouldn’t. While it’s taxing to write books, maybe the feds should impose a tax on authors who really ought to write more, the rationale being that we need their stories to stay sane–or mostly sane.

Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell (2004) and its alternate history of Britain and magic, is probably one of the best magic/fantasy novels anyone has written. We need more, much more because these books show us the world as it really exists. Perhaps Congress can convene a committee of dunces to learn why there’s been no sequel.

One pleasant surprise of 2012 was the appearance (without warning) of Morgenstern’s The Night Circus about a strange circus that appears without warning and spreads magic and humor in the towns where it manifests. The Starless Sea (2020) also captured our imagination with a magical world just as stunning as that of the circus.

One pleasant surprise of 2012 was the appearance (without warning) of Morgenstern’s The Night Circus about a strange circus that appears without warning and spreads magic and humor in the towns where it manifests. The Starless Sea (2020) also captured our imagination with a magical world just as stunning as that of the circus.

Perhaps the tactic Congress should take is that readers need more of these books for national security reasons. We know that rationale is always bullshit, but it seems to work.

Mark Helprin, at 76, has appeared with another novel that will help save us from the Ruskies, Hamas, and other bad people called The Oceans and the Stars. I like all of his work, but think nothing holds a candle to Winter’s Tale.

Mark Helprin, at 76, has appeared with another novel that will help save us from the Ruskies, Hamas, and other bad people called The Oceans and the Stars. I like all of his work, but think nothing holds a candle to Winter’s Tale.

Donna Tartt who–thank the good Lord is only 59–has always written at a snail’s pace. Congress can fix this because the country, as the Department of Homeland Security would say, “needs the security of books,” and that means that Tartt cannot take a few years off to play video games or watch “Survivor” and “Hells Kitchen” while the Pulitzer gathers dust on the shelves.

Donna Tartt who–thank the good Lord is only 59–has always written at a snail’s pace. Congress can fix this because the country, as the Department of Homeland Security would say, “needs the security of books,” and that means that Tartt cannot take a few years off to play video games or watch “Survivor” and “Hells Kitchen” while the Pulitzer gathers dust on the shelves.

We need the stories, but we wither on the vine when we’re stuck waiting for them for too long.

–Malcolm

I believe this because I read and I am f_cked up. If you read, you probably are, too.

I believe this because I read and I am f_cked up. If you read, you probably are, too.

I was a huge fan of the 1973 comedy-drama film directed by

I was a huge fan of the 1973 comedy-drama film directed by  Part of that draw came from “Love Story” (1970). The film earned a lot of money though it was much maligned for being a shameless tear-jerker. O’Neal and Candace Bergen starred in the 1978 sequel “Oliver’s Story.” I preferred “Barry Lyndon,” Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 historical drama that was drawn from William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844-era novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. The film received Oscar nominations and was notable for its cinematography.

Part of that draw came from “Love Story” (1970). The film earned a lot of money though it was much maligned for being a shameless tear-jerker. O’Neal and Candace Bergen starred in the 1978 sequel “Oliver’s Story.” I preferred “Barry Lyndon,” Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 historical drama that was drawn from William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844-era novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. The film received Oscar nominations and was notable for its cinematography. But then when I was tested to see if I had Celiac disease as part of this many-month-long attempt by doctors to find out what was causing my apparent stomach infection, I was happy to see that I don’t have the disease. For one thing, there’s no cure except for getting rid of gluten. For another, if I had a Celiac problem and went on a gluten-free diet immediately, it might take a couple of years to feel the results.

But then when I was tested to see if I had Celiac disease as part of this many-month-long attempt by doctors to find out what was causing my apparent stomach infection, I was happy to see that I don’t have the disease. For one thing, there’s no cure except for getting rid of gluten. For another, if I had a Celiac problem and went on a gluten-free diet immediately, it might take a couple of years to feel the results.

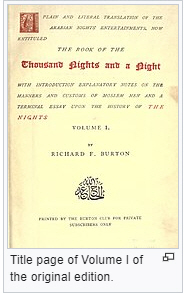

Scheherazade, the teller of the tales in The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, captured my imagination when I was in junior high school. The stories are fascinating. So was the idea of the narrator telling one story per night–but never quite ending it–to keep the king from killing her when a tale ends which he had threatened to do. Or perhaps it was her name that drew me in and never let me go.

Scheherazade, the teller of the tales in The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, captured my imagination when I was in junior high school. The stories are fascinating. So was the idea of the narrator telling one story per night–but never quite ending it–to keep the king from killing her when a tale ends which he had threatened to do. Or perhaps it was her name that drew me in and never let me go. I also had a copy of Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 symphonic suite “Scheherazade” based on the story. I had it on vinyl. It’s also around here somewhere, though I probably wore all the grooves off. My copy is older than the version shown here.

I also had a copy of Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 symphonic suite “Scheherazade” based on the story. I had it on vinyl. It’s also around here somewhere, though I probably wore all the grooves off. My copy is older than the version shown here. “THE BOOK OF THE Thousand Nights and a Night VOLUME V Translated by RICHARD F. BURTON Limited to one thousand numbered sets 1885 (London “Burton Club” edition), illustrated The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885), subtitled “A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments”, is a celebrated English language translation of “One Thousand and One Nights” (the “Arabian Nights”) – a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (8th−13th centuries) – by the British explorer and Arabist Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890). It stood as the only complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) of the “Arabian Nights” until 2008. “One Thousand and One Nights” (Arabic: كِتَاب أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة kitāb ʾalf layla wa-layla) is a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the Arabian Nights, from the first English language edition (1706), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales themselves trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folklore and literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān (Persian: هزار افسان, lit. A Thousand Tales) which in turn relied partly on Indian elements. Initial frame story of the ruler Shahryār (from Persian: شهريار, meaning “king” or “sovereign”) and his wife Scheherazade, (from Persian: شهرزاد, possibly meaning “of noble lineage”), and the framing device incorporated throughout the tales themselves. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while others begin and end of their own accord. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.”

“THE BOOK OF THE Thousand Nights and a Night VOLUME V Translated by RICHARD F. BURTON Limited to one thousand numbered sets 1885 (London “Burton Club” edition), illustrated The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885), subtitled “A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments”, is a celebrated English language translation of “One Thousand and One Nights” (the “Arabian Nights”) – a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (8th−13th centuries) – by the British explorer and Arabist Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890). It stood as the only complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) of the “Arabian Nights” until 2008. “One Thousand and One Nights” (Arabic: كِتَاب أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة kitāb ʾalf layla wa-layla) is a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the Arabian Nights, from the first English language edition (1706), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales themselves trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folklore and literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān (Persian: هزار افسان, lit. A Thousand Tales) which in turn relied partly on Indian elements. Initial frame story of the ruler Shahryār (from Persian: شهريار, meaning “king” or “sovereign”) and his wife Scheherazade, (from Persian: شهرزاد, possibly meaning “of noble lineage”), and the framing device incorporated throughout the tales themselves. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while others begin and end of their own accord. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.”

“Flowers for Algernon is a short story by American author Daniel Keyes, later expanded by him into a novel and subsequently adapted for film and other media. The short story, written in 1958 and first published in the April 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1960. The novel was published in 1966 and was joint winner of that year’s Nebula Award for Best Novel (with Babel-17).” – Wikipedia

“Flowers for Algernon is a short story by American author Daniel Keyes, later expanded by him into a novel and subsequently adapted for film and other media. The short story, written in 1958 and first published in the April 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1960. The novel was published in 1966 and was joint winner of that year’s Nebula Award for Best Novel (with Babel-17).” – Wikipedia My generation studied this novel in school, but by now–with all the movies available online and via satellite TV–I suppose more people have seen the 1968 movie film “Charlie” for which Cliff Robertson won the Best Actor Oscar and for which Stirling Silliphant won the Best Screenplay Oscar.

My generation studied this novel in school, but by now–with all the movies available online and via satellite TV–I suppose more people have seen the 1968 movie film “Charlie” for which Cliff Robertson won the Best Actor Oscar and for which Stirling Silliphant won the Best Screenplay Oscar. With more than five million copies sold,

With more than five million copies sold,

“Roberts is in fine form here. Her lush, ethereal world of ghosts and spirits is the perfect foil for Sonya’s down-to-earth, almost spartan manner. Another Roberts hallmark is on display: her continuing thematic exploration of how an individual defeats evil—not by acting alone, but by forming a community and harnessing its members’ strength and power for the coming battle.

“Roberts is in fine form here. Her lush, ethereal world of ghosts and spirits is the perfect foil for Sonya’s down-to-earth, almost spartan manner. Another Roberts hallmark is on display: her continuing thematic exploration of how an individual defeats evil—not by acting alone, but by forming a community and harnessing its members’ strength and power for the coming battle.

I very much like Thomas Hart Benton, especially his murals like the one shown here. One of my favorite old books on my shelves is his autobiography An Artist In America published in 1939. Sad to say, I cannot find the cover art online, but the cover shown here comes from an early edition. The cover, which shows some of his sketches, says that the book includes 64 sketches, representing “A sympathetic vigorous picture of America by one of her great artists.”

I very much like Thomas Hart Benton, especially his murals like the one shown here. One of my favorite old books on my shelves is his autobiography An Artist In America published in 1939. Sad to say, I cannot find the cover art online, but the cover shown here comes from an early edition. The cover, which shows some of his sketches, says that the book includes 64 sketches, representing “A sympathetic vigorous picture of America by one of her great artists.”

Most of us are aware that in 2015, the Department of the Interior finally recognized “Denali” as the official name for the mountain formerly called Mount McKinley. Alaska had been calling the Peak “Denali” for forty years already. Perhaps someday the world will officially recognize the Nepalese name “Sagarmatha” as the correct name for Mount Everest (shown here).

Most of us are aware that in 2015, the Department of the Interior finally recognized “Denali” as the official name for the mountain formerly called Mount McKinley. Alaska had been calling the Peak “Denali” for forty years already. Perhaps someday the world will officially recognize the Nepalese name “Sagarmatha” as the correct name for Mount Everest (shown here). While Sir. George Everest (4 July 1790 – 1 December 1866) had more to do with Sagarmatha (Goddess of the Sky) than President McKinley had to do with Denali (as a surveyor working on the connection between Northern India and Nepal), he never saw the mountain, said the word “Everest” would be difficult for people living in the area to pronounce, and didn’t believe the mountain should carry his name.

While Sir. George Everest (4 July 1790 – 1 December 1866) had more to do with Sagarmatha (Goddess of the Sky) than President McKinley had to do with Denali (as a surveyor working on the connection between Northern India and Nepal), he never saw the mountain, said the word “Everest” would be difficult for people living in the area to pronounce, and didn’t believe the mountain should carry his name. K2 in the Karakoram range, while not quite as tall as Everest, is a more difficult climb and, as such, is often called the “Savage Mountain.” Estimates are that one person dies for every four who summit the mountain. It used to be referred to as “Godwin-Austen after the English surveyor. None of the possible local names seems to stand out, but “Masherbrum” or “Chogori” might one day be considered as more appropriate.

K2 in the Karakoram range, while not quite as tall as Everest, is a more difficult climb and, as such, is often called the “Savage Mountain.” Estimates are that one person dies for every four who summit the mountain. It used to be referred to as “Godwin-Austen after the English surveyor. None of the possible local names seems to stand out, but “Masherbrum” or “Chogori” might one day be considered as more appropriate.