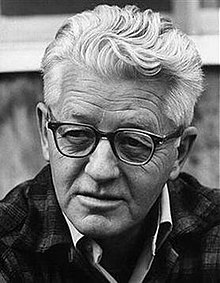

I read this novel soon after it came out in 1971 (and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1972) and, if I bothered to organize my books, it would definitely belong on my shelf of favorites. The novel is about a real historian Lyman Ward and Stegner (1909-1993) based it on the letters of author Mary Hallock Foote. Some say he shouldn’t have used actual passages from her work. He says he had permission to do so. The controversy remains amongst scholars.

I read this novel soon after it came out in 1971 (and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1972) and, if I bothered to organize my books, it would definitely belong on my shelf of favorites. The novel is about a real historian Lyman Ward and Stegner (1909-1993) based it on the letters of author Mary Hallock Foote. Some say he shouldn’t have used actual passages from her work. He says he had permission to do so. The controversy remains amongst scholars.

Wikipedia notes that “The title, seemingly taken from Foote’s writings, is an engineering term for the angle at which soil finally settles after, for example, being dumped from a mine as tailings.”

From the Publisher

An American masterpiece and iconic novel of the West by National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize winner Wallace Stegner—a deeply moving narrative of one family and the traditions of our national past.

Lyman Ward is a retired professor of history, recently confined to a wheelchair by a crippling bone disease and dependent on others for his every need. Amid the chaos of 1970s counterculture, he retreats to his ancestral home of Grass Valley, California, to write the biography of his grandmother: an elegant and headstrong artist and pioneer who, together with her engineer husband, made her own journey through the hardscrabble West nearly a hundred years before. In discovering her story he excavates his own, probing the shadows of his experience and the America that has come of age around him.

The Atlantic Monthly called the novel a “Cause for celebration…A superb novel with an amplitude of scale and richness of detail altogether uncommon in contemporary fiction.”

About the Author

“Wallace Stegner (1909-1993) was the author of, among other novels, Remembering Laughter, 1937; The Big Rock Candy Mountain, 1943; Joe Hill, 1950; All the Little Live Things, 1967 (Commonwealth Club Gold Medal); A Shooting Star, 1961; Angle of Repose, 1971 (Pulitzer Prize); The Spectator Bird, 1976 (National Book Award, 1977); Recapitulation, 1979; and Crossing to Safety, 1987. His nonfiction includes Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, 1954; Wolf Willow, 1963; The Sound of Mountain Water (essays), 1969; The Uneasy Chair: A Biography of Bernard DeVoto, 1974; and Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs: Living and Writing in the West (1992). Three of his short stories have won O. Henry Prizes, and in 1980 he received the Robert Kirsch Award from the Los Angeles Times for his lifetime literary achievements. His Collected Stories was published in 1990.” – Amazon Listing

In general, I try to support KIVA, Tibet, and the National Parks. This puts me on a list of people who would have to be rich to respond to all the projects that need funding. I support the International Campaign for Tibet because I believe that China’s illegal occupation of Tibet and its ongoing policy of erasing Tibetan culture and religion is one of the most noxious atrocities on the planet.

In general, I try to support KIVA, Tibet, and the National Parks. This puts me on a list of people who would have to be rich to respond to all the projects that need funding. I support the International Campaign for Tibet because I believe that China’s illegal occupation of Tibet and its ongoing policy of erasing Tibetan culture and religion is one of the most noxious atrocities on the planet. I support

I support  The Six-month tummy ache continues as the Gastroenterology Department runs a slew of tests. All are normal so far. This experience is pretty much like having a strong case of mono for six months (I’ve been there and done that). The adoption of the

The Six-month tummy ache continues as the Gastroenterology Department runs a slew of tests. All are normal so far. This experience is pretty much like having a strong case of mono for six months (I’ve been there and done that). The adoption of the  I’m re-reading One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. It’s been a while. And I still despise the first sentence. Among other things, this novel has had a strong influence on the magical realism genre. Wikipedia says “Since it was first published in May 1967 in Buenos Aires by Editorial Sudamericana, One Hundred Years of Solitude has been translated into 46 languages and sold more than 50 million copies. The novel, considered García Márquez’s magnum opus, remains widely acclaimed and is recognized as one of the most significant works both in the Hispanic literary canon and in world literature.”

I’m re-reading One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. It’s been a while. And I still despise the first sentence. Among other things, this novel has had a strong influence on the magical realism genre. Wikipedia says “Since it was first published in May 1967 in Buenos Aires by Editorial Sudamericana, One Hundred Years of Solitude has been translated into 46 languages and sold more than 50 million copies. The novel, considered García Márquez’s magnum opus, remains widely acclaimed and is recognized as one of the most significant works both in the Hispanic literary canon and in world literature.” Ah, “The Crown” has returned to finish out the rest of the season. In the episode we saw last night, Prime Minister Tony Blair tries to convince the queen that the monarchy is out of touch with everyday people and needs to modernize. She thinks not. Better to get rid of it completely, but then nobody asked me. Harry Potter fans will notice that the actress who’s playing the queen, Imelda Staunton, played the nasty Dolores Umbridge in the Hogwarts films. That fits.

Ah, “The Crown” has returned to finish out the rest of the season. In the episode we saw last night, Prime Minister Tony Blair tries to convince the queen that the monarchy is out of touch with everyday people and needs to modernize. She thinks not. Better to get rid of it completely, but then nobody asked me. Harry Potter fans will notice that the actress who’s playing the queen, Imelda Staunton, played the nasty Dolores Umbridge in the Hogwarts films. That fits. We watched the two-night “MasterChef Junior Home for the Holidays” and, as usual, find it hard to believe these kids can cook so well. When I was ten years old, I was playing cowboys and Indians in the backyard. But these children are turning out meals that could actually be served in a high-end restaurant. Ramsay gets his family into the act as commentators and judges. I wonder if he has to pay them. As usual with their kids’ shows, somebody gets a pie in the face. Guess who?

We watched the two-night “MasterChef Junior Home for the Holidays” and, as usual, find it hard to believe these kids can cook so well. When I was ten years old, I was playing cowboys and Indians in the backyard. But these children are turning out meals that could actually be served in a high-end restaurant. Ramsay gets his family into the act as commentators and judges. I wonder if he has to pay them. As usual with their kids’ shows, somebody gets a pie in the face. Guess who? I believe I’ve read most of the James Patterson series about Alex Cross. So, I’m looking forward to Alex Cross Must Die which was released last month. Typically–as a frugal Scot–I’m waiting for the price to come down before I buy it. From the publisher: “One of the greatest fictional detectives of all time (Douglas Preston & Lincoln Child) is in the sights of the Dead Hours Killer, a serial murderer on a ruthless mission.” I’m not exactly holding my breath about the outcome, but when I find a series of novels I like, it’s hard not to sell the house to pay for the latest installment.

I believe I’ve read most of the James Patterson series about Alex Cross. So, I’m looking forward to Alex Cross Must Die which was released last month. Typically–as a frugal Scot–I’m waiting for the price to come down before I buy it. From the publisher: “One of the greatest fictional detectives of all time (Douglas Preston & Lincoln Child) is in the sights of the Dead Hours Killer, a serial murderer on a ruthless mission.” I’m not exactly holding my breath about the outcome, but when I find a series of novels I like, it’s hard not to sell the house to pay for the latest installment. When I worked as a home manager at a developmental disabilities unit of the Illinois Department of Mental Health, people often asked if there was a career path. I told them that we kept advancing up the chain of command until we became patients. The same path exists for writers.

When I worked as a home manager at a developmental disabilities unit of the Illinois Department of Mental Health, people often asked if there was a career path. I told them that we kept advancing up the chain of command until we became patients. The same path exists for writers. While based on APA clinical practice guidelines, hospital treatment protocols vary depending on age, types of voices heard, and the persistence of hallucinations when manuscripts are set aside for the day. And yet, when all is written and done, the writer can only be discharged when s/he stops writing often with the assistance of Alprazolam 0.25 mg PRN.

While based on APA clinical practice guidelines, hospital treatment protocols vary depending on age, types of voices heard, and the persistence of hallucinations when manuscripts are set aside for the day. And yet, when all is written and done, the writer can only be discharged when s/he stops writing often with the assistance of Alprazolam 0.25 mg PRN.

Why is it that otherwise polite people (who are introduced as close friends) by relatives who live outside the South find it necessary to say with a perfectly straight face “I’m sorry” when we say we’re from Georgia? If they weren’t friends of my relatives, I could respond in all kinds of ways.

Why is it that otherwise polite people (who are introduced as close friends) by relatives who live outside the South find it necessary to say with a perfectly straight face “I’m sorry” when we say we’re from Georgia? If they weren’t friends of my relatives, I could respond in all kinds of ways. My wife, I think, wants to slap the shit out of these people. I understand that because she was born here in Georgia very near where we now live. I was born in California and lived in Oregon, New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania before settling in Georgia. The “I’m sorry” people don’t know any of this and if they did, it wouldn’t matter, because they’re living life looking for an excuse to say nasty things about Southerners.

My wife, I think, wants to slap the shit out of these people. I understand that because she was born here in Georgia very near where we now live. I was born in California and lived in Oregon, New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania before settling in Georgia. The “I’m sorry” people don’t know any of this and if they did, it wouldn’t matter, because they’re living life looking for an excuse to say nasty things about Southerners. I believe this because I read and I am f_cked up. If you read, you probably are, too.

I believe this because I read and I am f_cked up. If you read, you probably are, too.

I was a huge fan of the 1973 comedy-drama film directed by

I was a huge fan of the 1973 comedy-drama film directed by  Part of that draw came from “Love Story” (1970). The film earned a lot of money though it was much maligned for being a shameless tear-jerker. O’Neal and Candace Bergen starred in the 1978 sequel “Oliver’s Story.” I preferred “Barry Lyndon,” Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 historical drama that was drawn from William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844-era novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. The film received Oscar nominations and was notable for its cinematography.

Part of that draw came from “Love Story” (1970). The film earned a lot of money though it was much maligned for being a shameless tear-jerker. O’Neal and Candace Bergen starred in the 1978 sequel “Oliver’s Story.” I preferred “Barry Lyndon,” Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 historical drama that was drawn from William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844-era novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. The film received Oscar nominations and was notable for its cinematography. But then when I was tested to see if I had Celiac disease as part of this many-month-long attempt by doctors to find out what was causing my apparent stomach infection, I was happy to see that I don’t have the disease. For one thing, there’s no cure except for getting rid of gluten. For another, if I had a Celiac problem and went on a gluten-free diet immediately, it might take a couple of years to feel the results.

But then when I was tested to see if I had Celiac disease as part of this many-month-long attempt by doctors to find out what was causing my apparent stomach infection, I was happy to see that I don’t have the disease. For one thing, there’s no cure except for getting rid of gluten. For another, if I had a Celiac problem and went on a gluten-free diet immediately, it might take a couple of years to feel the results.