Every time I watch Billy Wilder’s 1950 black comedy “Sunset Boulevard,” I find myself nearly derailed when the numerous famous quotes from the film appear. As Smash Negativity says, while the film “delves into the depths of obsession and despair, it also sprinkles moments of humor throughout. From Norma Desmond’s [Gloria Swandon] over-the-top theatrics to Joe Gillis’ [William Holden] sarcastic and cynical remarks, the film finds levity amidst the darkness. It reminds us that even in the most somber of circumstances, a touch of wit and laughter can bring much-needed relief.”

Every time I watch Billy Wilder’s 1950 black comedy “Sunset Boulevard,” I find myself nearly derailed when the numerous famous quotes from the film appear. As Smash Negativity says, while the film “delves into the depths of obsession and despair, it also sprinkles moments of humor throughout. From Norma Desmond’s [Gloria Swandon] over-the-top theatrics to Joe Gillis’ [William Holden] sarcastic and cynical remarks, the film finds levity amidst the darkness. It reminds us that even in the most somber of circumstances, a touch of wit and laughter can bring much-needed relief.”

The quotes have been referenced in other films, as parodies or otherwise: “I am still big. It’s the pictures that got small.” “I’m ready for my close-up, Mr. DeMille.”

When strugggling screen writer William Holden, who is fleeing from the repo man, turns into a seemingly abandoned driveway leading to a seemingly abandoned mansion his first thought is hilding his car. But, he soon comes under the spell of nearly-forgotten film star Gloria Swanson who lavishes him with attention and gifts while hoping that he can help her write her big comeback film. Things don’t gso as planned for either of them.

When strugggling screen writer William Holden, who is fleeing from the repo man, turns into a seemingly abandoned driveway leading to a seemingly abandoned mansion his first thought is hilding his car. But, he soon comes under the spell of nearly-forgotten film star Gloria Swanson who lavishes him with attention and gifts while hoping that he can help her write her big comeback film. Things don’t gso as planned for either of them.

Pamela Hutchinson, in “Suset Boulevard: What Billy Wilder’s satire really tells us about Hollywood,” writes: “Former silent film star Desmond may be mad, but there is a grain of truth in what she says: Swanson was one of Paramount’s biggest stars even back when it was called Famous Players-Lasky, just as we are told Desmond was too. While Sunset Boulevard appears to attack the pretentions and excesses of the silent era, in fact its argument about the bad old days of Hollywood is more complicated than that. The horror at the heart of the film is that, as the studio system was starting to crumble, the beginnings of the industry were coming back to haunt it. Desmond’s pride mocks the fall of Hollywood just as it was teetering, rocked by the antitrust laws, the coming of TV and the communist witch-hunts.”

What the public saw in the films and their publicity was a bit different than what went on behind the scenes and corporate offices. If you haven’t lost your innocence about Hollywood already, watching “Sunset Boulevard” will take care of that transformation for you. As Huchinson says, “For all its humour, Sunset Boulevard is a bitter and queasy film, and the figure of Desmond is its greatest grotesque, a woman of 50 striving to be 25, surrounded by images of herself and entranced by her own face on a cinema screen.”

“They took the idols and smashed them, the Fairbankses, the Gilberts, the Valentinos! And who’ve we got now? Some nobodies!” – Norma Desmond

–Malcolm

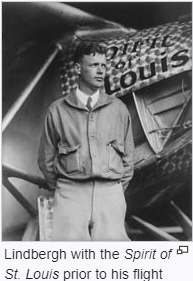

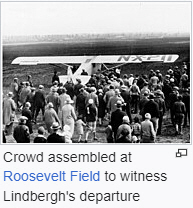

Lindbergh, who was 25, recounted his experience in his biography WE, which was published a few months after the historic New York to Paris flight and served as the film’s basis. Of course, a lot happened to Lindbergh between the time of his flight and the release of the film, including the 1932 kidnapping of his son and his widely publicized neutrality stance in discussions about the U.S. entering WWII. He apparently changed his mind after Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack.

Lindbergh, who was 25, recounted his experience in his biography WE, which was published a few months after the historic New York to Paris flight and served as the film’s basis. Of course, a lot happened to Lindbergh between the time of his flight and the release of the film, including the 1932 kidnapping of his son and his widely publicized neutrality stance in discussions about the U.S. entering WWII. He apparently changed his mind after Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack.

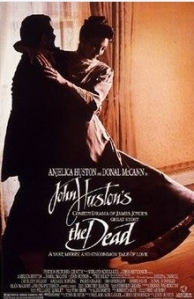

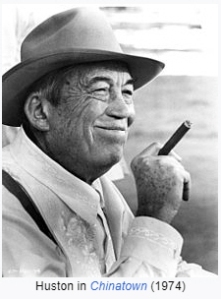

”’ONE by one we’re all becoming shades,’ says Gabriel Conroy, looking out into Dublin’s bleak winter dawn. Gretta, the wife he loves and suddenly realizes he has never known, lies asleep on the bed nearby. His own life now seems paltry: ‘Better pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age.’

”’ONE by one we’re all becoming shades,’ says Gabriel Conroy, looking out into Dublin’s bleak winter dawn. Gretta, the wife he loves and suddenly realizes he has never known, lies asleep on the bed nearby. His own life now seems paltry: ‘Better pass boldly into that other world, in the full glory of some passion, than fade and wither dismally with age.’ e died last August. He failed physically, but his talent was not only unimpaired, it was also richer, more secure and bolder than it had ever been. No other American filmmaker has ended a comparably long career on such a note of triumph.”

e died last August. He failed physically, but his talent was not only unimpaired, it was also richer, more secure and bolder than it had ever been. No other American filmmaker has ended a comparably long career on such a note of triumph.”

“Friendly Persuasion is a 1956 American Civil War drama film produced and directed by William Wyler. It stars Gary Cooper, Dorothy McGuire, Anthony Perkins, Richard Eyer, Robert Middleton, Phyllis Love, Mark Richman, Walter Catlett and Marjorie Main. The screenplay by Michael Wilson was adapted from the 1945 novel The Friendly Persuasion by Jessamyn West. The movie tells the story of a Quaker family in southern Indiana during the American Civil War and the way the war tests their pacifist beliefs.” –

“Friendly Persuasion is a 1956 American Civil War drama film produced and directed by William Wyler. It stars Gary Cooper, Dorothy McGuire, Anthony Perkins, Richard Eyer, Robert Middleton, Phyllis Love, Mark Richman, Walter Catlett and Marjorie Main. The screenplay by Michael Wilson was adapted from the 1945 novel The Friendly Persuasion by Jessamyn West. The movie tells the story of a Quaker family in southern Indiana during the American Civil War and the way the war tests their pacifist beliefs.” –  The film was drawn from the 1945 novel of the same name by Jessamyn West, a Quaker who wrote a plotless novel story about Quaker life. She was drawn into the making of the film through her willingness to pull together materials from her novel about the Civil War era that would make a cohesive story for the movie.

The film was drawn from the 1945 novel of the same name by Jessamyn West, a Quaker who wrote a plotless novel story about Quaker life. She was drawn into the making of the film through her willingness to pull together materials from her novel about the Civil War era that would make a cohesive story for the movie. I would have been ticked off paying for the tickets.

I would have been ticked off paying for the tickets. My wife hates “High Noon” and the theme song it rode in on. John Wayne didn’t like it either. I think it’s the perfect movie, not necessarily my favorite but perfect in the way it was put together: the music, the ticking block, the fact it was shot in real-time, and the fact (which the Duke hated) that normal citizens wouldn’t help a marshal fight off a gang of bad guys that would function like a SEAL team compared to people who mainly used guns for hunting.

My wife hates “High Noon” and the theme song it rode in on. John Wayne didn’t like it either. I think it’s the perfect movie, not necessarily my favorite but perfect in the way it was put together: the music, the ticking block, the fact it was shot in real-time, and the fact (which the Duke hated) that normal citizens wouldn’t help a marshal fight off a gang of bad guys that would function like a SEAL team compared to people who mainly used guns for hunting.

I’m thinking of this film today because I just learned that John Nichols died at 83 in November, and I’m rather embarrassed that I missed it at the time especially when such publications as The New York Times and

I’m thinking of this film today because I just learned that John Nichols died at 83 in November, and I’m rather embarrassed that I missed it at the time especially when such publications as The New York Times and

The American

The American

“For sheer, unadulterated terror there have been few films in recent years to match the quivering fright of Sorry, Wrong Number–and few performances to equal the hysteria-ridden picture of a woman doomed, as portrayed by Barbara Stanwyck.” — Cue Magazine.

“For sheer, unadulterated terror there have been few films in recent years to match the quivering fright of Sorry, Wrong Number–and few performances to equal the hysteria-ridden picture of a woman doomed, as portrayed by Barbara Stanwyck.” — Cue Magazine.

I’m biased in favor of Harris’ portrayal because I saw him once on the stage as well as in many movies and was used to his style (and his off-camera hijinks). He played a more ethereal Dumbledore than Gambon. Both were Irish and both were good in the role.

I’m biased in favor of Harris’ portrayal because I saw him once on the stage as well as in many movies and was used to his style (and his off-camera hijinks). He played a more ethereal Dumbledore than Gambon. Both were Irish and both were good in the role.