This novel focuses on the Dust Bowl, a time I think we’re slowly forgetting.

“The Bestselling Hardcover Novel of the Year.–Publishers Weekly

“The Bestselling Hardcover Novel of the Year.–Publishers Weekly

“From the number-one bestselling author of The Nightingale and The Great Alone comes a powerful American epic about love and heroism and hope, set during the Great Depression, a time when the country was in crisis and at war with itself, when millions were out of work and even the land seemed to have turned against them.

“’My land tells its story if you listen. The story of our family.’

“Texas, 1921. A time of abundance. The Great War is over, the bounty of the land is plentiful, and America is on the brink of a new and optimistic era. But for Elsa Wolcott, deemed too old to marry in a time when marriage is a woman’s only option, the future seems bleak. Until the night she meets Rafe Martinelli and decides to change the direction of her life. With her reputation in ruin, there is only one respectable choice: marriage to a man she barely knows.

“By 1934, the world has changed; millions are out of work and drought has devastated the Great Plains. Farmers are fighting to keep their land and their livelihoods as crops fail and water dries up and the earth cracks open. Dust storms roll relentlessly across the plains. Everything on the Martinelli farm is dying, including Elsa’s tenuous marriage; each day is a desperate battle against nature and a fight to keep her children alive.

“In this uncertain and perilous time, Elsa―like so many of her neighbors―must make an agonizing choice: fight for the land she loves or leave it behind and go west, to California, in search of a better life for her family.

“The Four Winds is a rich, sweeping novel that stunningly brings to life the Great Depression and the people who lived through it―the harsh realities that divided us as a nation and the enduring battle between the haves and the have-nots. A testament to hope, resilience, and the strength of the human spirit to survive adversity, The Four Winds is an indelible portrait of America and the American dream, as seen through the eyes of one indomitable woman whose courage and sacrifice will come to define a generation.”

Washington Post Review

“When The Four Winds picks up again in 1934, we’re deep in the Great Depression, and Hannah lets her story bake under the cloudless sky. A conspiracy of bad weather, bad agriculture and bad government gradually desiccates the entire area, bringing one farm after another to ruin.

“When The Four Winds picks up again in 1934, we’re deep in the Great Depression, and Hannah lets her story bake under the cloudless sky. A conspiracy of bad weather, bad agriculture and bad government gradually desiccates the entire area, bringing one farm after another to ruin.

B. B. Griffith was born and raised in Denver, Colorado and he still wanders Denver to this day. He’s the author of many best-sellers across several series, each unique, but with a common theme of modern magic and mystery. He’s been called an author of contemporary fantasy, an author of modern westerns, and an author of metaphysical thrillers. Sometimes all three at once. His novels have been called “rare and imaginative,” “full of lovable, memorable characters,” and his personal favorite: “A literary breath of fresh air.”

B. B. Griffith was born and raised in Denver, Colorado and he still wanders Denver to this day. He’s the author of many best-sellers across several series, each unique, but with a common theme of modern magic and mystery. He’s been called an author of contemporary fantasy, an author of modern westerns, and an author of metaphysical thrillers. Sometimes all three at once. His novels have been called “rare and imaginative,” “full of lovable, memorable characters,” and his personal favorite: “A literary breath of fresh air.”

Bonnie Jo Campbell is an American Writer living with her husband and donkeys in rural Michigan.

Bonnie Jo Campbell is an American Writer living with her husband and donkeys in rural Michigan.

ock at the door, Prophet Song forces us out of our complacency as we follow the terrifying plight of a woman seeking to protect her family in an Ireland descending into totalitarianism. We felt unsettled from the start, submerged in – and haunted by – the sustained claustrophobia of Lynch’s powerfully constructed world. He flinches from nothing, depicting the reality of state violence and displacement and offering no easy consolations. Here the sentence is stretched to its limits – Lynch pulls off feats of language that are stunning to witness. He has the heart of a poet, using repetition and recurring motifs to create a visceral reading experience. This is a triumph of emotional storytelling, bracing and brave. With great vividness, Prophet Song captures the social and political anxieties of our current moment. Readers will find it soul-shattering and true, and will not soon forget its warnings.’ – Esi Edugyan, Chair, Booker Prize.

ock at the door, Prophet Song forces us out of our complacency as we follow the terrifying plight of a woman seeking to protect her family in an Ireland descending into totalitarianism. We felt unsettled from the start, submerged in – and haunted by – the sustained claustrophobia of Lynch’s powerfully constructed world. He flinches from nothing, depicting the reality of state violence and displacement and offering no easy consolations. Here the sentence is stretched to its limits – Lynch pulls off feats of language that are stunning to witness. He has the heart of a poet, using repetition and recurring motifs to create a visceral reading experience. This is a triumph of emotional storytelling, bracing and brave. With great vividness, Prophet Song captures the social and political anxieties of our current moment. Readers will find it soul-shattering and true, and will not soon forget its warnings.’ – Esi Edugyan, Chair, Booker Prize. When Kirkus Reviews praises a book by saying, “An exceptionally gifted writer, Lynch brings a compelling lyricism to her fears and despair while he marshals the details marking the collapse of democracy and the norms of daily life. His tonal control, psychological acuity, empathy, and bleakness recall Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006). And Eilish, his strong, resourceful, complete heroine, recalls the title character of Lynch’s excellent Irish-famine novel, Grace (2017)” it’s certainly worth a look. Those of us who remember “The Troubles” (1960s-1990s) will feel an eerie sense of Deja Vu to the violent world of the Irish Republican Army.

When Kirkus Reviews praises a book by saying, “An exceptionally gifted writer, Lynch brings a compelling lyricism to her fears and despair while he marshals the details marking the collapse of democracy and the norms of daily life. His tonal control, psychological acuity, empathy, and bleakness recall Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006). And Eilish, his strong, resourceful, complete heroine, recalls the title character of Lynch’s excellent Irish-famine novel, Grace (2017)” it’s certainly worth a look. Those of us who remember “The Troubles” (1960s-1990s) will feel an eerie sense of Deja Vu to the violent world of the Irish Republican Army.

Scheherazade, the teller of the tales in The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, captured my imagination when I was in junior high school. The stories are fascinating. So was the idea of the narrator telling one story per night–but never quite ending it–to keep the king from killing her when a tale ends which he had threatened to do. Or perhaps it was her name that drew me in and never let me go.

Scheherazade, the teller of the tales in The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, captured my imagination when I was in junior high school. The stories are fascinating. So was the idea of the narrator telling one story per night–but never quite ending it–to keep the king from killing her when a tale ends which he had threatened to do. Or perhaps it was her name that drew me in and never let me go. I also had a copy of Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 symphonic suite “Scheherazade” based on the story. I had it on vinyl. It’s also around here somewhere, though I probably wore all the grooves off. My copy is older than the version shown here.

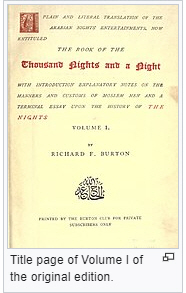

I also had a copy of Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 symphonic suite “Scheherazade” based on the story. I had it on vinyl. It’s also around here somewhere, though I probably wore all the grooves off. My copy is older than the version shown here. “THE BOOK OF THE Thousand Nights and a Night VOLUME V Translated by RICHARD F. BURTON Limited to one thousand numbered sets 1885 (London “Burton Club” edition), illustrated The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885), subtitled “A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments”, is a celebrated English language translation of “One Thousand and One Nights” (the “Arabian Nights”) – a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (8th−13th centuries) – by the British explorer and Arabist Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890). It stood as the only complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) of the “Arabian Nights” until 2008. “One Thousand and One Nights” (Arabic: كِتَاب أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة kitāb ʾalf layla wa-layla) is a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the Arabian Nights, from the first English language edition (1706), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales themselves trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folklore and literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān (Persian: هزار افسان, lit. A Thousand Tales) which in turn relied partly on Indian elements. Initial frame story of the ruler Shahryār (from Persian: شهريار, meaning “king” or “sovereign”) and his wife Scheherazade, (from Persian: شهرزاد, possibly meaning “of noble lineage”), and the framing device incorporated throughout the tales themselves. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while others begin and end of their own accord. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.”

“THE BOOK OF THE Thousand Nights and a Night VOLUME V Translated by RICHARD F. BURTON Limited to one thousand numbered sets 1885 (London “Burton Club” edition), illustrated The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885), subtitled “A Plain and Literal Translation of the Arabian Nights Entertainments”, is a celebrated English language translation of “One Thousand and One Nights” (the “Arabian Nights”) – a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age (8th−13th centuries) – by the British explorer and Arabist Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890). It stood as the only complete translation of the Macnaghten or Calcutta II edition (Egyptian recension) of the “Arabian Nights” until 2008. “One Thousand and One Nights” (Arabic: كِتَاب أَلْف لَيْلَة وَلَيْلَة kitāb ʾalf layla wa-layla) is a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the Arabian Nights, from the first English language edition (1706), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. The work was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, and South Asia and North Africa. The tales themselves trace their roots back to ancient and medieval Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folklore and literature. In particular, many tales were originally folk stories from the Caliphate era, while others, especially the frame story, are most probably drawn from the Pahlavi Persian work Hazār Afsān (Persian: هزار افسان, lit. A Thousand Tales) which in turn relied partly on Indian elements. Initial frame story of the ruler Shahryār (from Persian: شهريار, meaning “king” or “sovereign”) and his wife Scheherazade, (from Persian: شهرزاد, possibly meaning “of noble lineage”), and the framing device incorporated throughout the tales themselves. The stories proceed from this original tale; some are framed within other tales, while others begin and end of their own accord. The bulk of the text is in prose, although verse is occasionally used for songs and riddles and to express heightened emotion. Most of the poems are single couplets or quatrains, although some are longer.”

“Flowers for Algernon is a short story by American author Daniel Keyes, later expanded by him into a novel and subsequently adapted for film and other media. The short story, written in 1958 and first published in the April 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1960. The novel was published in 1966 and was joint winner of that year’s Nebula Award for Best Novel (with Babel-17).” – Wikipedia

“Flowers for Algernon is a short story by American author Daniel Keyes, later expanded by him into a novel and subsequently adapted for film and other media. The short story, written in 1958 and first published in the April 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1960. The novel was published in 1966 and was joint winner of that year’s Nebula Award for Best Novel (with Babel-17).” – Wikipedia My generation studied this novel in school, but by now–with all the movies available online and via satellite TV–I suppose more people have seen the 1968 movie film “Charlie” for which Cliff Robertson won the Best Actor Oscar and for which Stirling Silliphant won the Best Screenplay Oscar.

My generation studied this novel in school, but by now–with all the movies available online and via satellite TV–I suppose more people have seen the 1968 movie film “Charlie” for which Cliff Robertson won the Best Actor Oscar and for which Stirling Silliphant won the Best Screenplay Oscar. With more than five million copies sold,

With more than five million copies sold,