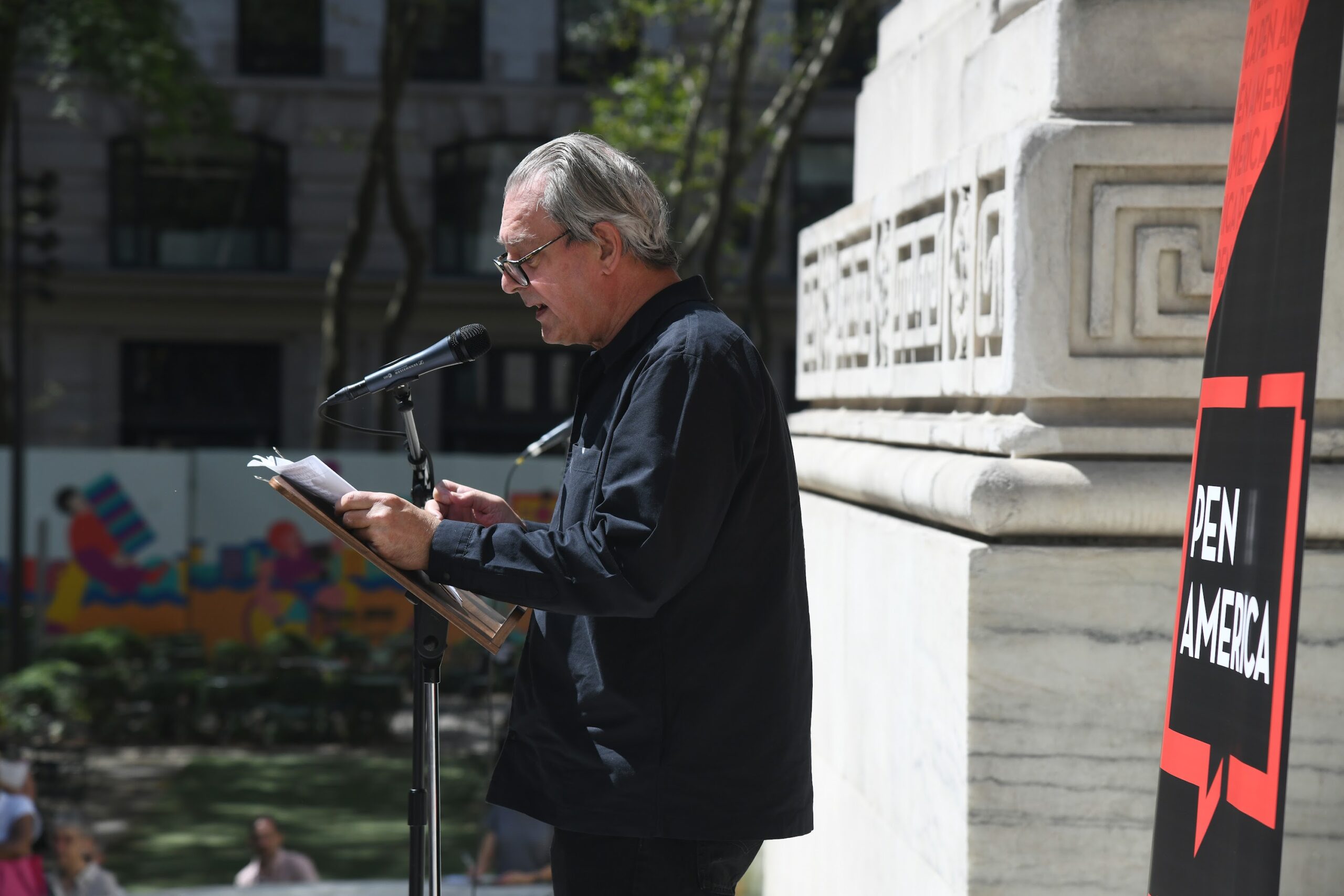

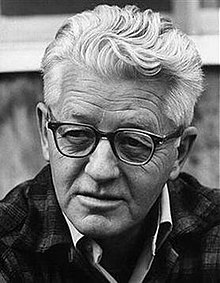

After mentioning a favorite of mine, Peter Matthiessen (May 22, 1927 – April 5, 2014) in yesterday’s post about The Land’s Wild Music, I thought, “Why not talk to Peter, see how he’s doing, find out who he likes in the college football bowl matchups, &c.” Easier said than done. It took me several hours to find my Ouija board. It was under the bed with my Radio Flyer wagon, an old baseball glove, and assorted monsters.

After mentioning a favorite of mine, Peter Matthiessen (May 22, 1927 – April 5, 2014) in yesterday’s post about The Land’s Wild Music, I thought, “Why not talk to Peter, see how he’s doing, find out who he likes in the college football bowl matchups, &c.” Easier said than done. It took me several hours to find my Ouija board. It was under the bed with my Radio Flyer wagon, an old baseball glove, and assorted monsters.

He was happy to have a little conversation and to let me now that he now sees two or three snow leopards every day, something he hoped for in his trek through the Tibetian Plateu in the 1973 with biologist George Shaller, recounted in his 1978 book The Snow Leopard. I’ve read a lot of Matthiessen’s work, but always return to The Snow Leopard as my favorite, winner of the National Book Award in 1979. The current edition has an introduction by Pico Iyer which is fine, but which I skip when reading old classics that are new to me.

I don’t want any help or advice when reading such words as these from the book: “The secret of the mountain is that the mountains simply exist, as I do myself: the mountains exist simply, which I do not. The mountains have no “meaning,” they are meaning; the mountains are. The sun is round. I ring with life, and the mountains ring, and when I can hear it, there is a ringing that we share. I understand all this, not in my mind but in my heart, knowing how meaningless it is to try to capture what cannot be expressed, knowing that mere words will remain when I read it all again, another day.”

I also especially liked At Play in the Fields of the Lord, Blue Meridian, African Silences, Far Tortuga, and In the Spirit of Crazy Horse. As for the last book on my list, Wikipedia says, “ Shortly after the 1983 publication of In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, Matthiessen and his publisher Viking Penguin were sued for libel by David Price, a Federal Bureau of Investigation agent, and William J. Janklow, the former South Dakota governor. The plaintiffs sought over $49 million in damages; Janklow also sued to have all copies of the book withdrawn from bookstores. After four years of litigation, Federal District Court Judge Diana E. Murphy dismissed Price’s lawsuit, upholding Matthiessen’s ‘freedom to develop a thesis, conduct research in an effort to support the thesis, and to publish an entirely one-sided view of people and events.’ In the Janklow case, a South Dakota court also ruled for Matthiessen. Both cases were appealed. In 1990, the Supreme Court refused to hear Price’s arguments, effectively ending his appeal. The South Dakota Supreme Court dismissed Janklow’s case the same year. With the lawsuits concluded, the paperback edition of the book was finally published in 1992.”

Shortly after the 1983 publication of In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, Matthiessen and his publisher Viking Penguin were sued for libel by David Price, a Federal Bureau of Investigation agent, and William J. Janklow, the former South Dakota governor. The plaintiffs sought over $49 million in damages; Janklow also sued to have all copies of the book withdrawn from bookstores. After four years of litigation, Federal District Court Judge Diana E. Murphy dismissed Price’s lawsuit, upholding Matthiessen’s ‘freedom to develop a thesis, conduct research in an effort to support the thesis, and to publish an entirely one-sided view of people and events.’ In the Janklow case, a South Dakota court also ruled for Matthiessen. Both cases were appealed. In 1990, the Supreme Court refused to hear Price’s arguments, effectively ending his appeal. The South Dakota Supreme Court dismissed Janklow’s case the same year. With the lawsuits concluded, the paperback edition of the book was finally published in 1992.”

The book focuses on Leoard Peltier’s 1977 murder conviction for purportedly killing two FBI agents during the agency’s misguided attack on the American Indian Movement. I followed the case and agreed with Matthiessen’s assessment. Peltier is still in prison. I don’t think he should be.

The book focuses on Leoard Peltier’s 1977 murder conviction for purportedly killing two FBI agents during the agency’s misguided attack on the American Indian Movement. I followed the case and agreed with Matthiessen’s assessment. Peltier is still in prison. I don’t think he should be.

Wikipedia writes: “In 2008, at age 81, Matthiessen received the National Book Award for Fiction for Shadow Country, a one-volume, 890-page revision of his three novels set in frontier Florida that had been published in the 1990s. According to critic Michael Dirda, ‘No one writes more lyrically [than Matthiessen] about animals or describes more movingly the spiritual experience of mountaintops, savannas, and the sea.'” I agree.

–Malcolm

“A special 50

“A special 50 “Beautifully rendered and deeply affecting, House Made of Dawn has moved and inspired readers and writers for the last fifty years. It remains, in the words of The Paris Review, both a masterpiece about the universal human condition and a masterpiece of Native American literature.” Birchbark Books. Momaday receiving the National Medal of Arts from George W. Bush in 2007

“Beautifully rendered and deeply affecting, House Made of Dawn has moved and inspired readers and writers for the last fifty years. It remains, in the words of The Paris Review, both a masterpiece about the universal human condition and a masterpiece of Native American literature.” Birchbark Books. Momaday receiving the National Medal of Arts from George W. Bush in 2007

One pleasant surprise of 2012 was the appearance (without warning) of Morgenstern’s The Night Circus about a strange circus that appears without warning and spreads magic and humor in the towns where it manifests. The Starless Sea (2020) also captured our imagination with a magical world just as stunning as that of the circus.

One pleasant surprise of 2012 was the appearance (without warning) of Morgenstern’s The Night Circus about a strange circus that appears without warning and spreads magic and humor in the towns where it manifests. The Starless Sea (2020) also captured our imagination with a magical world just as stunning as that of the circus. Mark Helprin, at 76, has appeared with another novel that will help save us from the Ruskies, Hamas, and other bad people called The Oceans and the Stars. I like all of his work, but think nothing holds a candle to Winter’s Tale.

Mark Helprin, at 76, has appeared with another novel that will help save us from the Ruskies, Hamas, and other bad people called The Oceans and the Stars. I like all of his work, but think nothing holds a candle to Winter’s Tale. Donna Tartt who–thank the good Lord is only 59–has always written at a snail’s pace. Congress can fix this because the country, as the Department of Homeland Security would say, “needs the security of books,” and that means that Tartt cannot take a few years off to play video games or watch “Survivor” and “Hells Kitchen” while the Pulitzer gathers dust on the shelves.

Donna Tartt who–thank the good Lord is only 59–has always written at a snail’s pace. Congress can fix this because the country, as the Department of Homeland Security would say, “needs the security of books,” and that means that Tartt cannot take a few years off to play video games or watch “Survivor” and “Hells Kitchen” while the Pulitzer gathers dust on the shelves. BB: (Those who aren’t listening move on to the next question but a few rephrase the question.) No, seriously what would you be doing?

BB: (Those who aren’t listening move on to the next question but a few rephrase the question.) No, seriously what would you be doing? pseudonym because anyone who told that story under his own name would have ended up wherever Judge Crater ended up when he disappeared in 1930. Actually, his picture rather messes up this post, but such is life. Anyhow, nobody ever knew I wrote the “tell-all” about everyone in or near Hollywood.

pseudonym because anyone who told that story under his own name would have ended up wherever Judge Crater ended up when he disappeared in 1930. Actually, his picture rather messes up this post, but such is life. Anyhow, nobody ever knew I wrote the “tell-all” about everyone in or near Hollywood.

Shortly after the 1983 publication of

Shortly after the 1983 publication of  The book focuses on Leoard Peltier’s 1977 murder conviction for purportedly killing two FBI agents during the agency’s misguided attack on the American Indian Movement. I followed the case and agreed with Matthiessen’s assessment. Peltier is still in prison. I don’t think he should be.

The book focuses on Leoard Peltier’s 1977 murder conviction for purportedly killing two FBI agents during the agency’s misguided attack on the American Indian Movement. I followed the case and agreed with Matthiessen’s assessment. Peltier is still in prison. I don’t think he should be.

“I can no longer travel, can’t meet with strangers, can’t sign books but will sign labels with SASE, can’t write by request, and can’t answer letters. I’ve got to read and concentrate. Why? Beats me.” – Annie Dillard,

“I can no longer travel, can’t meet with strangers, can’t sign books but will sign labels with SASE, can’t write by request, and can’t answer letters. I’ve got to read and concentrate. Why? Beats me.” – Annie Dillard,

Several days ago, I

Several days ago, I